Mental health is such a sensitive topic, yet when it comes to media coverage of celebrity wellbeing, things can get a little... personal. Is the way we talk about mental health in the media damaging our perception – and the wellbeing – of those with ill mental health?

Celebs. They can’t really win, can they? Whether they’re trying to raise awareness for issues that affect many of us and we jump on a poor turn of phrase, or they’re just trying to live their lives, and get the support any one of us would seek out in a similar crisis, they still come under fire.

Earlier this year, Game of Thrones star Sophie Turner, best known for her role as Sansa Stark, responded to an insensitive tweet from opinion-dividing daytime talkshow host, Piers Morgan, after he agreed with controversial comments said in The Sun claiming “Celebs are trying to make mental health fashionable”.

Or maybe they have a platform to speak out about it and help get rid of the stigma of mental illness which affects 1 in 4 people in UK per year. But please go ahead and shun them back into silence. Twat. https://t.co/mvddYPjcht

— Sophie Turner (@SophieT) January 9, 2019

Let’s take a moment for that to sink in. The host of one of the UK’s most watched morning shows, said it is “100% true” that celebrities are trying to make mental health fashionable. You know, mental health – that thing that we all have. Or perhaps he meant mental illness, or mental ill health. After all, just one in six of us have experienced a common mental health problem over the past week within the UK. One in four of us will experience a mental health problem over the next year.

Mental health problems are one of the main causes of overall disease burden worldwide. Depression is thought to be the second leading cause of disability worldwide, as well as a major contributor to suicide. We lose a fifth of our working days each year to depression and anxiety. 10% of English people will experience depression at some point during their lifetime, and nearly 8% of Britain meet the criteria for an anxiety or depression diagnosis. In the space of just 10 years, over 18,000 people with mental health problems completed suicide in the UK.

But sure. Celebrities are the exception.

Part 1 : People who think it’s okay to make jokes about mental illness, I feel you must be lucky, because surely you don’t understand or can’t comprehend what it is like to have or know someone with an illness like this.

— Sophie Turner (@SophieT) January 9, 2019

The importance of talking about mental health

The Mental Health Foundation say that talking about how we are feeling can help us to stay in good mental health, as well as to deal with challenging times. The more we talk about our feelings, the better we feel able to cope with our problems. Through talking regularly about our health and wellbeing, we can help dispel and reduce the stigma, showing others who may be struggling in silence that it’s OK for them to speak up and seek help too.

In their recently launched campaign, mental health charity Mind teamed up with McVitie’s to spread the word about their Let’s Talk initiative. Research revealed 82% of us believe meaningful conversations with someone about our worries and concerns are beneficial to our mental wellbeing, yet one in five of us spend less than 10 minutes a day having meaningful conversations at home. Nearly half of us keep our worries and concerns to ourselves.

While opening up can be tricky - especially with someone who many not understand – speaking with an expert can offer the chance to open up without fear of judgement. Talking therapies can help with a wide variety of issues, from addiction or anger issues, past abuse to physical illness.

Any one of us could speak to our GP for a referral for mental health support, call a helpline such as Samaritans to speak with someone, seek charity support and referrals, or seek out a private counsellor. Yet when celebrities try to do the same, the media turns on them. Why is that?

Celebrities mental health in the media

When Game of thrones star Kit Harington, best known for his role as Jon Snow, checked into a Wellness Centre to work on personal issues, some traditional media sources were less than sensitive with their coverage.

The Mail Online ran with headlines claiming Kit “broke down and bowed out”, highlighting his earnings from the globally successful show alongside his reported trip to “rehab to deal with stress and alcohol issues”.

Highlighting the cost of the private facility Harington attended, instead of focusing on the positives of the star seeking help and support, the publication asked insensitively phrased questions around “So what’s wrong with Kit?”, going on to mention his “empty schedule” now the near decade-long show has come to an end.

Alluding to a potential alcohol addiction throughout, the journalist goes on to say in one instance “at least he had a legitimate excuse: he was apparently at the stag do before his wedding”.

While many other traditional news sources chose to go with more sensitive headlines, it does bring in to question: are the media being responsible with their reporting, or are they trying to sensationalise people’s personal lives when they are at their most vulnerable? Do we, as members of the public, have a right to pry into the lives of our favourite celebs? Or is our insatiable curiosity only fanning the flames and encouraging insensitive coverage?

In 2018, as presenter Ant McPartlin continued his recovery from drug addiction, headlines were quick to focus on how it would impact our TV viewing. While McPartlin’s history with rehab was skimmed over, the focus quickly returned to uncertainties around the autumn’s upcoming series of I’m A Celebrity, and whether his co-host, Declan Donnelly would go on to host alone or with a new co-host.

A further publication chose to highlight a “furious rant” from a friend of McPartlin’s then wife. The highly personal tweets had received just over a dozen responses prior to being picked up by the publication, where the friend publicly said:

“I do believe drugs and alcohol addiction is an illness but’s it’s not an excuse for such utter disregard for good humans. Go back to rehab… in a few years you might come to realise the pain you have caused and the irreparable wounds that can’t heal, and you will no doubt be full of remorse. But something tells me it might be too late.”

The article included no information on alcohol abuse or addiction, the long-lasting affects on individuals, family members, or loved ones. It didn’t include information for readers who may themselves be experiencing addiction problems, advice on how others can seek support, or any statistics on the prevalence of alcohol or painkiller addiction.

One in five of us have consumed more than the recommended 14 units of alcohol over the past week. Hospitals continue to struggle under the strain of alcohol-related admissions, with nearly 338,000 between 2017/18 alone. NHS statistics put the number of alcohol-related deaths at nearly 6,000 in 2017.

What do publications hope to achieve through highlighting what could have been a personal conversation, a private moment of anger between two people? Would more of us have benefitted from the reframing of such coverage, to how people can seek help and support? Or is our momentary schadenfreude that much more valuable as clickbait?

Singer James Arthur has spoken openly about his struggles with anxiety for years. When in early 2019, Arthur decided to pull out of a charity gig for the Teenage Charity Trust hours before he was due to go on stage, coverage seemed to be more sensitive (though headlines still erred on the fine clickbait line).

Many of his fans took to social media to share messages of support and love for the singer’s choice to put his own mental health first. “Nothing more important than your health - sending love your way!” one fan, Grace Davies wrote. Fellow singer-songwriter, Josh Franceschi, shared words of support to Arthur’s original tweet. “Chin up lad. Nothing more important than our health x”

— James Arthur 🦉 (@JamesArthur23) March 28, 2019

It makes us ask: why do some celebrities get coverage offering words of support and love when they admit they need help, whilst others appear judged for seeking the same? What makes some coverage compassionate, whilst others focus purely on the negatives?

Are we able to better sympathise with some mental illnesses such as anxiety – something many of us may have felt in some form or another – compared to addiction, something that is easier to condemn from the safety of our sofas and anonymity of our screens?

Media coverage is forever

Frankly, experiencing ill mental health sucks. Whether you have a brief ‘bad patch’ or are trying to cope with an ongoing issue, dealing with mental illness can be stressful, emotional, and an all-round intense experience.

While many chose to become advocates, speaking out about their experiences with diagnosis and specific conditions, for celebrities who live their lives on the world stage, no moment of vulnerability is forgotten. There’s no real chance to make the choice as to if those painful moments will become public or not, and the media? They never forget.

Britney Spears’ spiral that saw her attack photographers, become involved in a hit-and-run accident, and memorably, shave her head, is still the subject of memes and headlines over a decade later. In a 2008 interview for the documentary “For the Record” with MTV, Spears spoke about the incident:

“People thought that it was me going crazy and stuff like that, but people shave their heads all the time. I was going through a lot, but it was just kind of like me going through a little bit of rebellion, or feeling free, or shedding stuff that had happened, you know?”

In the years following the incident, Spears went on to lose custody of her children, her own involuntary hospitalisation in a psychiatric ward, and control of her finances were handed over to her father. Following long-running success performing in Las Vegas, earlier this year Spears went on to cancel her Vegas show due to “mental health issues” as she went on an “indefinite work hiatus”. She continues to have no control over her estate over a decade since the initial court ruling.

It’s undeniable that Britney’s public meltdown was newsworthy. Here we had a young woman, highly sexualised from a young age by the media and those shaping her music career, reaching breaking point. Yet doesn’t it say something about us, that we have reduced her experience to a series of memes? What does it say about us, that we still use her situation to feel better about our own?

Influencer mental health in the media

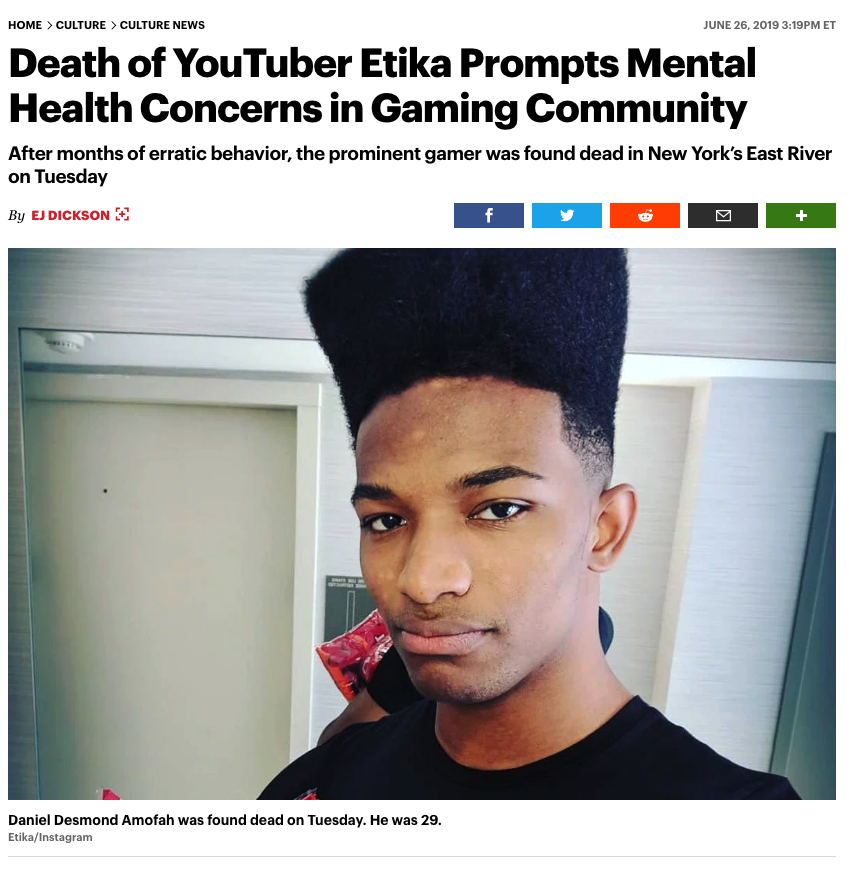

Just this week, YouTuber Daniel Desmond Amofah, better known as Etika, was found dead in New York. Following months of erratic behaviour with fans expressing concern for his wellbeing, the popular gamer’s death has sparked a debate around the mental health and wellbeing of others within the gaming and YouTube communities.

Shortly after posting a video discussing his suicidal thoughts (which was subsequently removed for violating terms of service), concerned subscribers and fans across his channels expressed their concerns. Following the news that police had recovered Amofah’s body after he had completed suicide, many news sources went on to include details on his death.

How the media report on mental health can hugely influence public attitudes towards mental health. Numerous charities offer guidelines, advice and suggested practises around how we can speak of such sensitive issues in a compassionate, factual way, without further stigmatising those experiencing mental ill health or adding to pre-existing misconceptions.

Since the news has been confirmed, some fans’ initial skepticism that the deleted video was a publicity stunt have turned to many sharing their own stories and struggles with mental health, as well as sharing favourite memories of Etika’s career.

The Mental Health Media Charter, launched in 2017, sets out seven simple guidelines to help journalists and publications ensure that both the imagery and language they use is “responsible, genuinely educational and stigma-reducing”.

Created with the help of the Samaritans, Mental Health First Aid (MHFA) England, and Beat, the charter has since been signed by bloggers, YouTubers, journalists, and organisations (including those of us here at Happiful).

The Samaritans explain that celebrity deaths can draw a lot of media coverage, which can significantly increase the risk of imitational suicidal behaviour. Guidelines recommend the media avoids explicit details of suicide or, ideally, not reporting the method at all. Avoiding speculation, placement on the front page, or making the story a lead are all advised. Yet many sites have led with the story, sharing both details of how Amofah completed suicide.

Other YouTubers and Influencers are expressing their concerns that Etika’s death is a sign of a wider problem within the influencer community. eSports gamer Juan Debiedma ‘Hungrybox’ expressed both his condolences, and his feelings that “influencer mental health is something that we need to address more often.”

I’m speechless, this is actually wild.

— hungrybox (@LiquidHbox) June 25, 2019

RIP Etika. I honestly feel that influencer mental health is something that we need to address more often.

This is tragic. https://t.co/g1ByRj05Lj

In 2018, numerous YouTubers begun opening up about burn out, mental health, and the importance of therapy. Sean McLoughlin, better known as JackSepticEye, collaborated in a series of videos with therapist Kati Morton to discuss the impact of creatives overworking themselves, their subsequent stress, and healthy strategies they could incorporate.

Many influencers and content creators such as McLoughlin create multiple updates for fans, day-in day-out, for years without taking a substantial break.

Speaking of his own experience as a YouTuber, McLoughlin said: “It’s like a really fast treadmill that just keeps going. My upload schedule was the only thing keeping me on it. Then I took a week off, I took a break, and it’s like everything slows down... it gave me that change... I feel like I’m going at my own pace again now. It’s OK to take a break.”

Is there a right answer?

We know talking about our mental health can help to reduce stigma, open up conversations, and help us (and those we care about) to find the help and support they need. We also know that too many details can be triggering, can risk imitational behaviour, or may even, in some people’s eyes, glorify mental ill health.

While by its very nature, fame reduces much of the privacy and anonymity celebrities can expect, but is it really fair that such deeply personal and painful moments in their lives are immortalised, scrutinised, and picked through with insensitive language, for all the world to read?

Perhaps the answer lies in our language, and how we choose to use it. Language – the words we use, how we use it – can shape our thoughts and ideas. Studies have shown changing the language in how a question is phrased can affect the way the event is remembered.

How we speak about things – be it describing how positive our morning was, or bemoaning a weekend lost to bad weather – can affect not only how we feel in that moment, but can pass on some of our enthusiasm or discontent to those we are sharing it with. As linguist Maxine explains, in the same way we learn a language through listening to others, we also learn the beliefs and behaviours that accompany what we say.

Our power as readers

As readers, we many not feel like we have the power to change the phrasing used by the media to report on mental illness and suicide. But in reality, we have much more power than we might think.

Next time you spot a clickbait headline calling out your favourite celeb, next time you see a presenter belittling someone’s personal experiences with mental ill health or their courage to speak out and share their story, next time you see a mean-spirited meme making fun of someone in a low or unaware moment – think before you click.

Your views, your time, your energy, your replies – they’re all a currency of sorts. The less attention these damaging voices get, the more we focus on lifting up those who seek to truly help those who are struggling, who genuinely want to help reduce the stigma around mental ill health.

Our anger and vitriol can feel cathartic in the moment, yet it can often fan the flames. By giving them our time, we validate their words. We give them worth in the eyes of advertisers. We send the message to editors ‘yes, keep commissioning more stories like this!’

It’s time we refocus our energy on spreading positive mental health coverage. Let’s bring the focus back to helping, not taking voyeuristic pleasure in other’s misfortune. Let’s start treating celebrities mental health struggles like we would hope to be treated – with kindness, compassion, dignity, and words of encouragement.

If you have been affected by any of the topics discussed within this article, please know that there are people out there who care, are willing to listen, and are here to support you. You can get help by:

If you are in crisis and are concerned for your safety, call 999 or go to your local A&E.

Calling Samaritans on 116 123 for free, anytime, or emailing them at jo@samaritans.org. Contact the SANEline between 6pm-11pm for support and information on 0300 304 7000.

If you feel more comfortable talking online, the Campaign Against Living Miserably (CALM) line for men offer a webchat between 5pm-12am or can be called on 0800 58 58 58.

To find a private counsellor or therapist near you, visit Counselling Directory or enter your details in the box below to find a qualified expert near you.

Comments