For every person diagnosed with cancer, £178 is spent on research per year. For mental illness, the figure is just £8. MQ wants to change that

"It’s hard to define when mental health research, as we would understand it, emerged,” says Sophie Dix, Director of Research at MQ – the UK’s only charity funding research into mental illnesses. Founded in 2013, MQ’s vision is simple: “To create a world where mental illness is understood, effectively treated, and ultimately prevented.” Yes, it’s simple, but it’s also revolutionary. For MQ, heightened awareness of mental illnesses has to be met with medical and psychological support – and when government funding remains limited, it’s down to charities to fill the gaps.

“The UK is fortunate to have vibrant and largely positive public discussion about mental health – and, thanks to the NHS, it remains one of the few nations in the world with a commitment to provide mental health support to its citizens,” says Cynthia Joyce, CEO of MQ. “But service improvements can’t possibly meet all the mental health needs out there. MQ is working to help the media focus on research advances and getting innovative new ideas into practice.”

It’s a cause to support, and one that makes total sense considering the steep increase in the number of people affected by mental illness in the UK. Which begs the question, why hasn’t a charity like this existed before? “Funnily enough,” says Cynthia, “with respect to mental health research, we’ve found that most people think someone else has it covered. There is lots of good work going on in the research sector, some government funded, some from industry. But mental health is complex and needs tackling on a huge scale if we hope to see real change take place.”

“Mental illness has been described in texts dating back over two millennia, but it wasn’t until the 19th century that psychology and psychiatry emerged,” Sophie says. “Many of the earliest drugs to treat mental illnesses were discovered by chance last century.” And there hasn’t been much progress since. Sophie explains: “In the last 30 years, academia and the pharmaceutical industry have struggled to find new treatments for mental illness, and little in the way of new medicines.”

But, even as a young organisation, MQ is seeing incredible breakthroughs. “One of our scientists is interested in how hormones affect how well talking therapies for anxiety work. She found that, dependent on the phase of a women’s menstrual cycle, there are better times of the month to deliver treatment than others.”

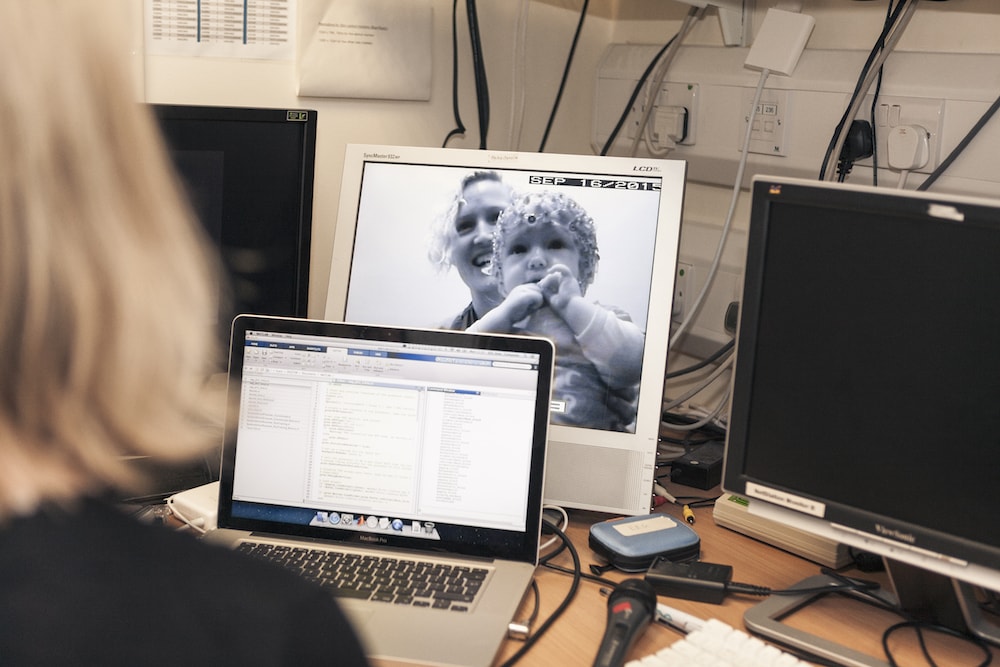

Photography | Andy Tyler

MQ’s star-studded campaign, We Swear, is an invitation to the public to say enough is enough – our understanding and treatment of mental illness has got to be improved, and research is integral to seeing real change. Why “swearing”? “The vision for this arose naturally from discussions with stakeholders, patients, families, and GPs all struggling to name the feelings of frustration and desire for a commitment to make a change happen,” says Cynthia.

The campaign dares people to swear to take a stand for pioneering mental health research, through fundraising and raising awareness. To date, over 600 people have taken up the challenge. Among the supporters are Mel C, Rag’n’Bone Man, Arlene Phillips, and many more celebrity heavyweights.

Why the need for celebrity endorsement? “A good friend of mine once said that in the field of medical research, not having a celebrity can kill you,” says Cynthia. “It’s a bit dramatic – but there is no doubt that celebrities of all kinds are role models in our lives. And they cut through the noise with their messages.”

Photography | Andy Tyler

Even when funding is available, there are several challenges to researching mental health, namely because it is such a broad subject with countless variables such as genetics, poverty, socialisation and biology. MQ prides itself on what it calls a “multidisciplinary” approach to research.

“There are many different types of science that can be used to understand more about mental illness and how we can treat it,” says Sophie. “We need the social sciences to understand how life experience and the society that we live in may impact mental health. We need psychology to understand behaviour and mental processes, and we need neuroscience to understand the mechanics and biology of the brain.”

In order to achieve this, MQ takes steps to fund early-career scientists, with the aim of encouraging them to commit to working together to tackle mental illness.

Only in recent times has the increased visibility of mental illness encouraged both the public and professionals to re-evaluate the hard distinction between mental and physical health. But despite this, there is still a lot of uncertainty about the ways in which they interact. “People with severe mental illness are likely to die on average 20 years earlier than those without. Also, people with physical illnesses such as diabetes and heart disease are more likely to have mental illness, and if they have mental illness their physical health symptoms are likely to be worse. We simply don’t understand why,” says Sophie.

But, despite this clear link, the difference in spending on research into physical over mental illnesses is shocking. “Despite fantastic efforts by the royal family, politicians and celebrities, stigma remains a big issue,” says Sophie. “This means that in terms of research, the public don’t put the same pressure on the government to invest more, nor is there the same level of charitable giving towards research.”

For Cynthia, the disparity in funding is also a lot to do with how we identify our own mental health. “The simple fact is that many of us don’t realise when we need help – nor do we know what to do when someone asks for help, whether a child or adult.” She adds: “We need to make mental health literacy a basic part of health education, and we need to do it now.”

Comments