A father tells, for the first time, how he struggled to come to terms with his child’s non-binary sexuality, depression, and suicidal impulses – and how their journey to understanding showed him how to become a better parent

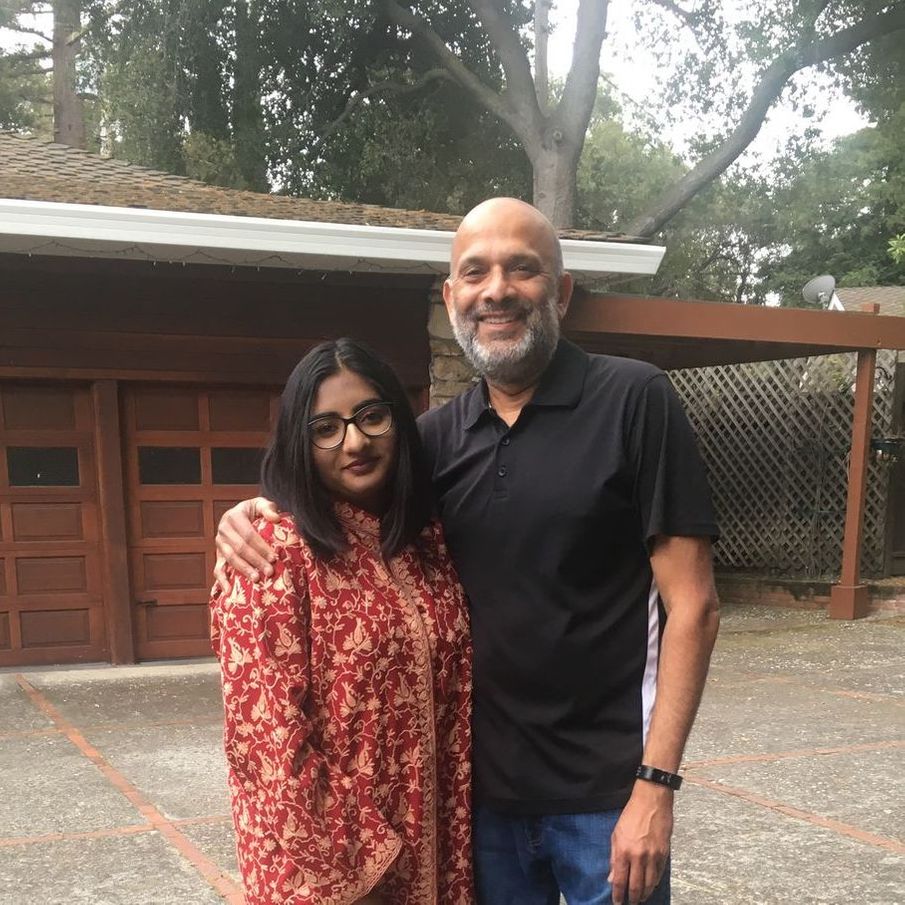

“You two created this beautiful miracle with the help of God!” exclaimed a stranger, looking at our four-month-old, Kav, in 2002. That miracle of ours, who recently turned 18, tried to take their life earlier this year. This is the story of how Kav was pushed to that brink, and my journey coming to accept Kav’s gender identity, and mental illness. I hope what I share for the first time here, will help others.

As a child, Kav was happy, sociable, and a joy to be with. How then, in the span of a decade, could they be diagnosed with depression and anxiety?

The three years of middle school turned out to be some of the worst in Kav’s life. Kav was, and still is, a deeply caring, empathetic person. Middle school girls can be mean when they gang up against a “goody two shoes” child. The very qualities we cherish came to be Kav’s nemesis with a clique of girls. Kav withdrew into a shell – being present, but not visible.

In a small class of about 20, Kav’s drama teacher included everybody in a play, but forgot to cast Kav. That insensitive act, the inability to fit in or create meaningful friendships, and the bullying, chipped away at Kav’s self-confidence. To this day, they are working on reclaiming their sense of self.

Around the same time, Kav was questioning their gender identity and sexuality. I vividly recall 12-year-old Kav saying: “Appa, I don’t feel that way about boys… the way I am supposed to…” While I didn’t dismiss Kav’s feelings, I failed to give it importance or understand that it was one of the reasons they were bullied.

None of this affected Kav’s academic performance, which met my expectations as a father. Kav also secured admission to two private high schools, neither of which they were keen on attending. Kav picked the school of my choice, presumably yielding to pressure from me.

The summer before high school, Kav cut themselves for the first time. On the advice of a friend of ours, Kav started seeing a therapist and psychiatrist. That my child preferred discussing their troubles with strangers was difficult for me to digest.

Within six months, Kav started taking antidepressants. I hated the idea of my child needing medication for mental illness, but hoped that Kav would quickly be weaned off them. I also thought high school would be different, and that with therapeutic help, Kav would bounce back to normal. But in the end, neither came to pass.

In August 2016, during a regular therapy session, Kav’s therapist called me into the room. I knew something was amiss as soon as I walked in. Kav had cut themselves with an intent to end their own life. I was devastated. Kav saw the deep agony in my face as their therapist discussed what happened. She advised additional treatment in the form of an Intensive Outpatient Program (IOP).

That week was one of the worst of our lives. We had to process the fact that our child had taken their suicidal thoughts to the next level. By not acknowledging the suicide attempt, I naively tried to will the problem away, while Kav developed a deep sense of guilt for putting us through this. The weight of being a burden likely played a significant role in Kav’s behavior, as they tried to show us a happier version of themselves while continuing to suffer in silence.

The IOP program provided Kav with additional coping skills. Kav met other high school students in similar situations, and had an opportunity to interact with some of them in a safe setting, allowing them to make friendships among kindred souls.

I am doing my best to give up my biases around mental illness and re-learn everything about depression

Kav continued to explore gender identity, and at one point declared they were “gender fluid, bi-romantic, and asexual”. I was completely lost in that complicated definition.

During this time, Kav found solace in reading young adult fiction. They started a YouTube channel, xreadingsolacex, where they review books, and discuss their gender identity and mental illness.

The year that followed actually felt normal, making me believe that we may have seen the worst. I was foolish to underestimate the vicious nature of depression and its continued grip on Kav.

Kav graduated in 2019 with good grades, but only due to a superhuman effort. Kav told me: “It takes twice or thrice the effort for someone with depression to accomplish the same task compared to someone like you.” I heard what Kav said, but never listened.

After graduation, Kav enrolled in a local community college. I was relieved that Kav chose to continue their higher education. However, community college did nothing to improve Kav’s depression.

Kav cut themself again, just before Christmas. They shared this with us in January. Sitting together as a family, we worked on improving the strained lines of communication, and things started looking up. Then came the fateful Monday in February when Kav overdosed. How did Kav come to a point of absolute hopelessness, where they felt this was the only option they had?

Depression is a brutal ailment that saps the will of a person, one happy strand at a time. It is like rot that steadily eats away at a wooden platform causing it to collapse one fine day, without warning, at the lightest of touches.

It is hard to identify one specific cause for Kav’s breakdown. Friends and family who carelessly misgendered them frustrated Kav for not respecting who they really are. The drama teacher who forgot to cast Kav, and the high school principal who pitied them for being an atheist, both failed Kav. The bullies who damaged their self-esteem.

Tellingly, I failed Kav as a dad through my own inadequacies. I failed to willingly acknowledge Kav’s gender identity. I underestimated the gravity of their mental illness. It was I who named them Kavya, a beautiful word that means poetry in Tamil. When they wanted to be known as Kav, I ought to have realised that a name is but a gift parents give their child; that the child should have the freedom to change it if the gift does not work for them.

Everything I did for Kav stemmed from my abundant love. I realise today that my love must have felt stifling, with conditions attached to it. I failed to have the sagacity to realise good parenting goes beyond providing a good education.

Kav is exceptionally gifted, and has much to contribute to the world. Their considered views on social justice, gender equity, and proper representation, demonstrate wisdom far above their age. Currently, Kav is in a Partial Hospitalisation Program and getting personalised treatment and I am fervently hopeful that they will heal. Their recovery may not be linear, but I am optimistic.

Kav’s therapist said: “What was, and is, cannot be”. It is a deeply insightful message, but not just for Kav. I am no longer skirting the issue; instead I am doing my best to give up my biases around mental illness and re-learn everything about depression. I am learning to untether my burdensome love for my child. And I stand ready to support my non-binary lesbian child, unconditionally.

Rachel Coffey | BA MA NLP Mstr, says:

S Suresh’s story is one of bravery. It is always difficult to watch someone we love struggling with depression. We want to fix them. And having a child who has suicidal tendencies brings up so many feelings – especially guilt, as parents wonder if this is their fault.

Love though, is never a burden. We just need to be aware of when our desire for a child to get well might add to the pressure they are feeling. Giving someone space when we want to be constantly by their side, is possibly the most generous yet challenging act of all.

Comments