Dr Antonis Kousoulis from the Mental Health Foundation shares information and advice on suicide prevention and explains just how important a friendly conversation or some simple kindness can be

Sometimes we really want to support another person who seems to be struggling, but we don’t know where to start and worry we might make things worse. Suicide seems frightening and overwhelming, so it’s natural for many of us to want to ‘look the other way’ – how could you possibly talk anyone out of it? But there is good news: just talking with another person and showing you care can be an incredible help.

Testimonies from people who have come close to ending their lives, and the many people who have helped them, show that even when a suicidal act may be very near, a friendly conversation or some simple kindness can make a critical difference.

In other words, you can do a lot to prevent suicide.

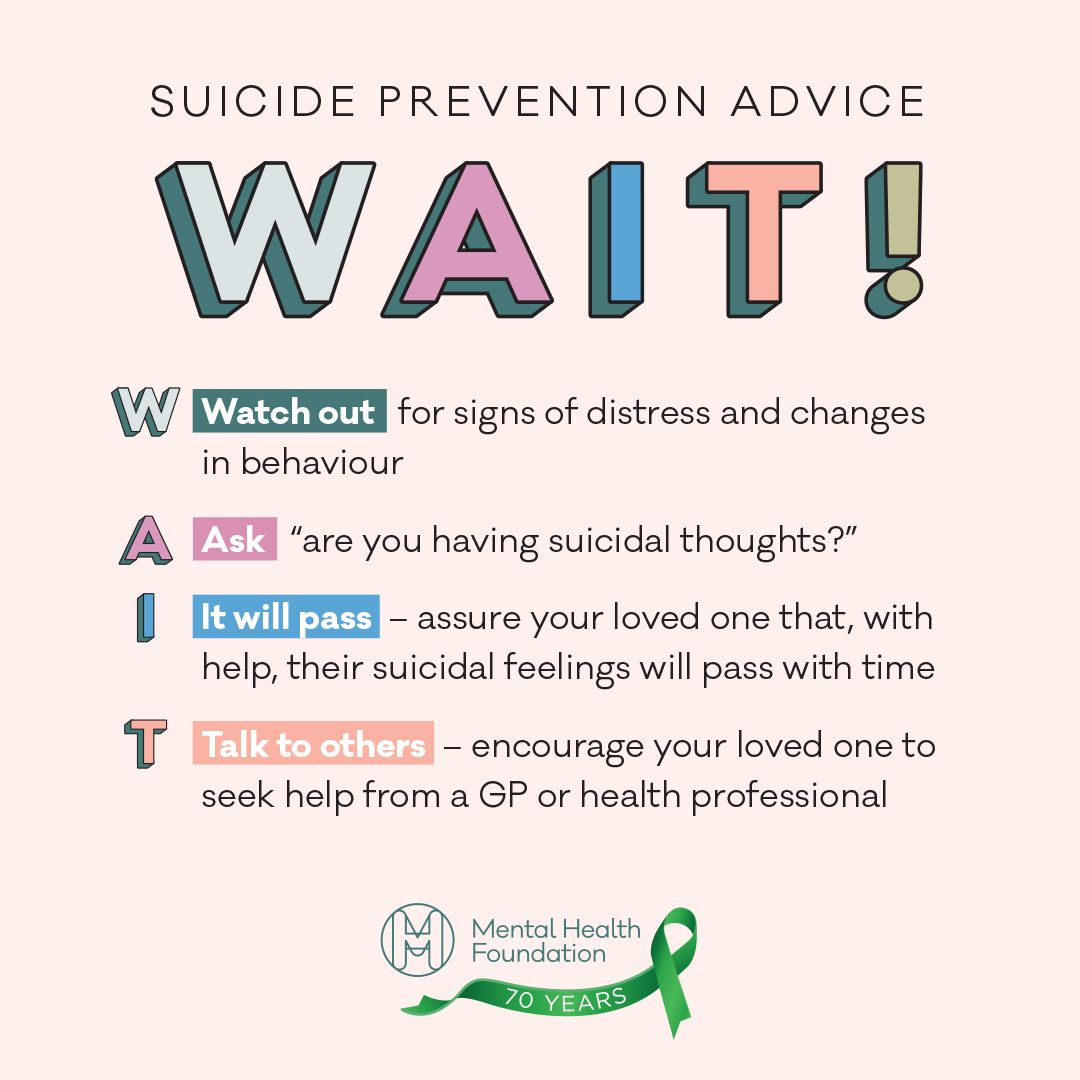

At the Mental Health Foundation (MHF), we want to help people support others to WAIT. With this acronym, we are summarising some key ideas that will help you support another person who may be having a crisis.

W stands for Watch: Look out for signs of distress and uncharacteristic behaviour. For instance, withdrawing from contact with other people, excessive quietness, irritability, uncharacteristic outbursts and talking about death or suicide.

A stands for Ask: Are you having suicidal thoughts?

You might worry that asking about suicide will put the idea into someone’s head, or encourage them towards it. But the opposite is true: asking about it makes suicide less likely and may start a life-saving conversation. Being able to talk about how they are feeling will help the other person feel acknowledged, validated, better.

I stands for “It will pass”: Assure the other person that their suicidal feelings will pass with time. It may not seem like it now, but it can get better.

T stands for Talk to others: Encourage the other person to seek help from a GP or other health professional.

How can you help someone who is suicidal

It’s very natural to feel nervous, afraid or uncomfortable about talking to someone else who seems in distress and asking them about suicide. It’s not something we normally talk about. Try to remember that being able to talk about how they are feeling is likely to help them, as will the care and concern you show them.

The Samaritans have some great advice about how to be a good listener in this situation, including:

- Focus your attention to the other person. Put away your phone, make eye contact and show you are listening.

- Resolve not to talk about yourself – this is all about the other person.

- Give them time to talk – don’t rush them. They may need plenty of time to put what they’re feeling into words. If there’s silence for a while, don’t feel you have to fill it.

- Don’t judge what they say (for instance, by telling them they’re wrong or being selfish or stupid), which may make them feel worse and also unable to keep talking.

- Instead, show that you are listening and trying to understand. One way to do this is to summarise what you think they are saying and let them correct you if you’ve misunderstood.

- Use open questions, such as ‘how are you feeling now?’ rather questions with a yes/no answer, and encourage the other person to expand on what they’ve said, for instance by saying ‘tell me more about that?’

- Check they know where to get help or specific advice for their situation.

Telephone helplines and mental health support

If the person you’re supporting seems so distressed that they are in immediate danger of harming themselves, then try to keep them talking and seek emergency help. Call 999 or offer to go with the person to Accident & Emergency.

Please don’t underestimate how big an impact supporting another person who feels like ending their own life could have on you. Put some time aside to debrief and find support for yourself

Rethink Mental Illness also offers sound advice about how to help, including how you can help during and after any visit to a hospital A&E department.

If you prefer to learn through e-learning rather than reading, then this free, 20-minute online training about how to support another person who may want to end their life may be for you. It’s provided by the Zero Suicide Alliance (of NHS organisations, companies and individuals).

There are also telephone helplines to call, for people who are feeling they want to end their lives - and also for those supporting them or concerned about them:

- The Samaritans offer a free 24/7 service. Call them on 116 123. You can also email jo@samaritans.org.

- CALM (Campaign Against Living Miserably) have a helpline (0800 585858) and also webchat open from 5pm until midnight, to support men.

- Papyrus aims to prevent suicide among people under 35 and offers support to them and anyone concerned that a young person may be feeling suicidal. Call on 0800 068 4141 or email pat@papyrus-uk.org

A really important point is: please don’t underestimate how big an impact supporting another person who feels like ending their own life could have on you. Put some time aside to debrief and find support for yourself. Talking to family or friends may be enough, or you might want to call a supportive helpline or take some time out to focus on yourself.

Suicide: The UK picture

What is all too clear is that at present, thousands of people in the UK are not getting the help they need to survive periods of emotional crisis.

More than 6,500 people took their own lives during 2018, according to the most recent official figures for the UK. This means that the suicide rate rose for the first time since 2013. Some of the rise may be due to a change in the way coroners in England and Wales record the cause of a person’s death, but it is too soon to know how much.

Men in their late 40s continue to be at the highest risk of all, although women in the same age group are also at increased risk of taking their own lives.

All of this may leave you feeling that we’re all powerless to help anyone feeling so bad that they would like to stop being alive. The good news is, you’d be wrong

Disturbingly, too, girls and young women aged between 10 and 24 have also shown up in the latest figures about suicide in the UK. Although very few of them take their own lives, the number doing so has increased significantly since 2012.

At the MHF, we were concerned by these trends but not surprised, because they are in line with other indicators of how people are feeling, such as rates of self-harm and polling evidence about painful experiences which include shame.

The personal story that leads up to each suicide is always complex and unique, and it will often stretch back over many years.

However, the evidence does also suggest that economic austerity contributes towards suicide rates, with financial uncertainty, unemployment and persistent inequality all having an influence, along with wider factors including ill-health, loneliness and discrimination.

As for why more girls and young women are taking their own lives, again the explanation is never simple, but likely contributory factors include violence, domestic abuse and trauma.

Another influence may well be the feeling of never being good enough - a feeling which is becoming more common when faced with the flood of images of perfect-looking people that surges through social media, advertising and pornography. Research from the MHF found that young women, in particular, are especially vulnerable to feeling ashamed of themselves in the face of such imagery.

All of this may leave you feeling that we’re all powerless to help anyone feeling so bad that they would like to stop being alive. The good news is, you’d be wrong.

Comments