Alastair Campbell’s colourful and candid life has seen him scale the heights of journalism and politics, with two breakdowns over the course of 30 years. Reflecting on a past which included rebuilding his career, he tells Happiful his fears of an "anxiety epidemic"

Alastair Campbell

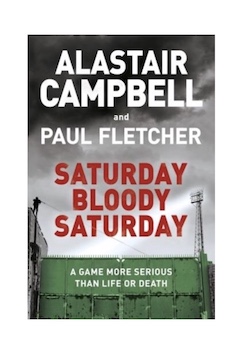

You’re talking to me [laughs]. Today, I’ve done radio interviews about Brexit, so you’re talking to an anti-Brexit campaigner and the editor-at-large of the New European. I’ve had a conversation with my publisher about my upcoming novel, Saturday Bloody Saturday, and my co-author Paul Fletcher about its launch. I try to do something everyday to promote mental health, be it writing, speaking, advising, consulting, strategising.

Err, breakdown. [Incidentally, earlier this month, Alastair and Neil went to see ‘Network’, a play chronicling a TV presenter who has a mental breakdown on air.] I think about that moment of explosion, when my mind sort of cracked. [When Alastair experienced his first breakdown, he was arrested for his own safety and taken to a hospital in Glasgow.]

Looking back, there was a big build-up that I didn’t see at the time. I didn’t feel anything; I thought I was invincible. My mind couldn’t cope with it, and it just exploded.

My partner Fiona would say no. I was at a newspaper called Today and she was saying to them: “He’s cracking up.” My bosses replied: “No, he’s brilliant, he’s a whirlwind and he’s doing clever things.” So, I don’t hold them responsible.

There was always a very on-edge side of me that you had to be wary of, but it gave me this energy and creativity

Looking back, when I was with the Mirror beforehand, there was a big drinking culture. I certainly felt supported there and in politics when I went back to work after my breakdown. I felt people were conscious that I’d had a bad experience and was trying to rebuild myself.

Tony Blair didn’t realise how bad my depression was at times. I never felt I couldn’t pull out or raise a problem if I had to. However, I think a lot of people in the workplace feel they can’t even raise their problem.

I did, and that’s why it took me so long to say yes. I remember saying to Tony: “Look, I have cracked up before.” I was drinking before though, and I wasn’t in 1994. But the pressures that made me crack before would only be greater.

Deep down, I did feel more resilient. But at the same time, I did have worries about it. Tony was so determined and said: “I know all about your history, and I don’t mind.”

Alastair Campbell

I don’t think it was a level of understanding; he had known me for several years. Having seen how I had recovered from the breakdown, gone to the bottom of the Mirror and rose up to Political Editor, he had perhaps thought about it. I raised my mental health history with him and asked: “What if it happened again?” He was confident that it wouldn’t.

That said, when he wrote his own book, I did take him to task as he actually wrote a passage that said when it comes to mental illness, there are those who are crazy and those who are a bit crazy, and it gives them this amazing energy and creativity – and that I was one of them. I wrote a blog saying hold on a minute, that’s not how it works.

I think he meant there was always a very on-edge side of me that you had to be wary of, but it gave me this energy and creativity. There is something in that. But you can’t say there are these mad people and creative mad people. It’s much more complicated than that.

We all have mental health. Every single one of us. Some of us get ill, some of us get very ill.

We should, but a lot of people don’t.

People think I’ve always been a fitness fanatic, but I haven’t; I was a heavy smoker, big drinker. You wouldn’t necessarily think smoking and mental health are linked, but smoking is creating illness, creating anxiety, and drink definitely does too. I think the drinking culture in areas I know well – media, politics and journalism – is much less than it was. But I think with the general public, it’s embedded. We are a drinking nation. You used to see MPs bouncing off walls when they went into the House of Commons to vote.

My big worry is that the government is using the mental health awareness battle as a substitute for policy

I think it could be. My eldest son Rory, who’s 30 now, said at the very start of the social media rise: “This is a disaster. It’s terrible for people.”

You have real relationships, and then you have these virtual relationships. I think there is some good in it, but schools are now banning phones. Teachers say that kids are looking at them all the time.

I was on a train, and there was a young woman on her phone looking at herself and putting pictures out constantly. It was like another universe. Nothing wrong with that on one level, but I don’t know the good it’s doing.

Alastair and Fiona

Maybe my skin has grown too thick. It doesn’t bother me at all. I see the context; there does seem to be a lot of hatred and anger out there for everybody. I think it must put people off from going into politics.

Not at all, it’s not good to stop saying what you think. I’m not one of those who puts themselves in the Katie Hopkins and Toby Young category where that person wants to be talked about. I am interested in saying what I think, and like a robust argument and engaging on that. People are more understanding when you do nail your colours to the mast.

Theresa May and Jeremy Hunt talk the talk. I think the expressions of mental health as a priority are good. But, you have to judge them by what’s been delivered. I don’t think the delivery has been good.

My big worry is that, we’re winning the battle for better understanding and awareness, but more and more people are thinking: “Maybe I am in need of mental health support?” Then they’re finding the services aren’t there. I wish they would stop saying it’s a priority and not doing anything about it.

They have got to match their words with policy. There’s loads of stuff that could be done. I accept money is going to be tight, but my big worry is that they are using the awareness battle as a substitute for policy.

I would like them to say: “We all have mental health.” I would like them to stop thinking only of mental illness; we have to invest in people’s mental health. That would take me into areas of education and sport – the preventative side of things. I don’t think they do nearly enough on that.

In terms of when they’re making decisions on funding, stop making it the easy area that always gets cut first. Build a long-term plan. There’s definitely something going on with young people and anxiety; if you’re not making sure young people get the help they need, it’ll cost you more in the long-term.

Funnily enough, Fiona and I were walking to an anti-Brexit meeting, and on the way there we saw this guy who was clearly having a psychotic breakdown.

I would like them to stop thinking only of mental illness; we have to invest in people’s mental health

He was talking to things that weren’t there and there was a stream of nonsense coming out of his mouth. I said: “Have you got any friends I can call?” I got through to voicemails, and then rang 999 for an ambulance.

They take you through a long checklist and I was worried I couldn’t restrain him and that he might hurt himself. Then I was told: “OK, if you can just keep him stable and calm, we’ll have an ambulance there in two to three hours.” I thought they were kidding me.

I would say I’m in a reasonably good place. I still get depressed. I still have low moods. I still get a bit manic. I still see a psychotherapist. There was a period in my life where I saw him a couple of times a week, but now I’d say it’s more like months apart. I have developed my own strategy by focusing on the things that matter: my family. For me, creativity and writing help.

Saturday Bloody Saturday will be my 14th book, including the diaries. Writing is a form of therapy.

The diaries are quite useful for helping me figure out what to do in the future. I am self-aware enough, and know one of the reasons I get hired to talk to people is because of what I did. I have tried to use that in a positive way.

They approached me years ago and were aware of me talking publicly about my mental health. At the time I was very involved with a leukaemia charity, and I said: “I’ll do it, but I don’t want to get drawn away from them.” As time has gone on, I realised Mind and mental health really motivates me, so I have got more and more involved: writing, talking, broadcasting, lobbying with government and businesses who take the wellbeing of their employees seriously – and give them time off when they need it.

I was speaking at one of the big banks recently, and they have their own mental health counsellors in-house working full-time, and staff are encouraged to see them.

My brother Donald, who had schizophrenia all of his adult life, died last year and my children were very aware of that, plus my own issues.

I would say I am in a reasonably good place, I still get depressed, I still have low moods. I still get a bit manic. I still see a psychotherapist

My daughter Grace has been very vocal in talking about her anxiety. My son Calum is very active in Alcoholics Anonymous; he’s had issues with drink which he’s dealt with brilliantly. I do remember saying to them when I first started seeing the psychiatrist: “I have this depression, and you must never think of it as a bad thing.”

There’s no doubt parents worry more about their kids than anything. I hope it helps that both of their parents are very open about mental health.

It would probably be: “Calm down a bit. Stop drinking, stop smoking,” and probably: “Listen to what the people around you are saying.”

At the same time, Stephen Fry once said having bipolar is horrible, but if somebody offered him a button he could press to stop being manic, he’s not sure he would press it.

If you said I could press a button and never experience depression again, I think I would take it. But at the same time, if you said as a result of that I might not have as many ideas for campaigning and books and be less creative, I would be worried.

[Pause] I think I probably would. But that being said, I know exactly what Stephen Fry meant.

Alastair Campbell is an Ambassador for Time to Change, also for Mind and Rethink Mental Illness, and patron of the Maytree Suicide Respite Centre in London.

Alastair’s latest novel, Saturday Bloody Saturday, centres on a football manager in the 70s who brings his struggling team to London, where the shadow of IRA terrorism stirs.

Out now, available on Amazon and Alastair’s website: www.alastaircampbell.org

Comments