You’re browsing through Facebook. Suddenly you see something familiar. You freeze. Your heart is pounding. It’s a topless photo you sent your ex. You feel exposed. Degraded. Helpless. Your blood runs cold. What happens next?

Writing | Rebecca Thair & Kathryn Wheeler

In a leaked document from Facebook this year, it was revealed that the social media giant investigated almost 54,000 potential cases of revenge porn on the platform over a single month.

This crime – and it is now illegal in the UK – ruins lives. Victims find their private photos and videos distributed without their consent to porn sites, posted across social media, sent to family and colleagues, and used to blackmail them.

Commonly known as “revenge porn”, this crime isn’t limited to vengeful exes. It can include “upskirt” pictures, sextortion, or hacking into a phone with private images contained on it, and there are an estimated 2,000 sites solely dedicated to publishing these images. The term “image-based sexual abuse” reflects the global epidemic more appropriately, depicting the severity and variety of the crime.

Many will remember the celebrity iCloud hacking scandal of 2014, where private images of stars including Jennifer Lawrence and Kate Upton were stolen and released on the forum 4chan. High-profile cases bring the issue to the headlines, but there are countless incidents destroying lives that don’t make the papers.

Happiful spoke with survivors of this abuse, as well as legal professionals, helplines, academics and activists to give you a full overview of the impact of this crime, your cyber rights, and what to do if someone threatens to,

or does, distribute private, intimate images of you.

The Survivor

"I was born and raised in Ontario, Canada and it was there, seven years ago, that I met my ex-boyfriend. We were best friends and became a couple five months later. I was 17 and he was 18 when I got pregnant with our daughter. We were very young, but excited.

After our daughter was born in January 2012, my ex started to change. He became very abusive. I was terrified, but felt trapped because we had a child together.

When I turned 18, his behaviour changed again. He asked if I wanted to make a porn video. I told him no. He told me that if I didn’t do it, he would take our daughter away from me and send me to a women’s shelter. I felt like I had no choice. If I wanted to keep my daughter in my life, I had to do it. So we did.

A few days later, we got into a bad fight and he threatened to post the video. We kept fighting and then he left for hours. When he came back, he told me he’d uploaded the video to the internet. I felt broken inside.

In August 2012, my ex was arrested. I took the chance and ran away with my seven-month-old daughter to our local women’s shelter, where we stayed until we got our new home.

In May 2013, I got full custody of my daughter, and an order against him stating that he couldn’t be around us.

Some years later, I found a couple on Youtube named “Bria and Chrissy”. One of them was going through a revenge porn case; it felt amazing to see someone who had gone through a similar situation fighting for what she believes in. She gave me the courage to take legal action. I started to build my case, but it felt like I was getting nowhere. I was losing hope, until our local victim witness centre suggested I should report it to the police.

I reported it in 2014, but there was no law against revenge porn at the time. In 2015, the law was passed, and the video was investigated. On the 21 September 2017, the police informed me that because the video doesn’t show our faces, there isn’t sufficient evidence that it is actually me and my ex in the video. This means they can’t take the video down, and my ex won’t be charged.

When I found out, I was completely devastated and felt lost. I’m currently in counselling to help me move on and heal. From the start, I was prepared that this outcome was a huge possibility. But just because my case didn’t work out, doesn’t mean yours won’t.

I’m now 23 and in college, working towards my dream career: working with LGBTQ youth. After some time, I came out, and now identify as lesbian. I’m engaged, and my fiancée is amazing with my daughter, and my daughter loves her too. I still suffer with PTSD and depression after the abuse, but I take it one day at a time. For anyone going through a similar situation I just want to say, don’t give up."

The Barrister

We speak to Frances Ridout, deputy director of the Queen Mary Legal Advice Centre, which runs SPITE – a specialist service dedicated to helping victims of image-based sexual abuse

WHAT IS SPITE?

We launched SPITE (Sharing and Publishing Images to Embarrass) in February 2015, just before the Criminal Justice and Courts Act came into force in April 2015. This statute made it against the law to distribute a private sexual image of another person, where the person in the image hasn’t given their consent. We give free, one-to-one client advice. We partnered with Revenge Porn Helpline, who do incredible work getting images removed from online platforms, so we cross-refer a lot of clients.

With SPITE appointments, anyone under 18 needs to be accompanied by a parent or guardian. A lot of our clients come to us just because they want to know their legal options. There’s a lot of variety in the type of cases we’re contacted about; we were initially surprised at the number of male clients. The cases are varied and can range from an ex-partner distributing images for revenge, to sextortion and blackmail, or someone’s sexuality being revealed – perhaps in communities where this isn’t widely accepted.

Revenge Porn Helpline get a lot of calls where the person doesn’t know who the perpetrator is, and we are able to work with clients who are in this position. From launching SPITE, we realised there was a real need to do preventative work, so we launched a community project called SPITE for Schools in 2015. We send teams of three undergraduate law students into secondary schools, to deliver a bespoke workshop designed for the pupils, under the supervision of a qualified barrister or solicitor. Last year we worked with 11 schools, and next year we’re aiming for 18.

WHAT ARE YOUR RIGHTS?

It is against the law to distribute a private sexual image of another person without their consent

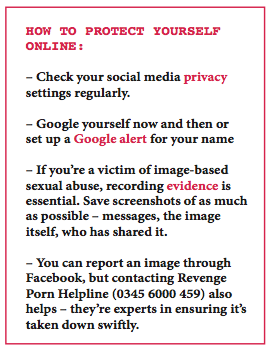

If someone shares an explicit image of you without your consent, there are two main legal avenues you can go down: criminal or civil action. It is against the law to distribute a private sexual image of another person without their consent. There’s a two- year maximum prison sentence. The difficulty, and this is also the case with civil action, is evidence, i.e. proving the offence. This is why we advise victims to keep screenshots and save as much evidence of the offence as possible. It’s also important to remember that under the new criminal statute, every act of disclosure is equally liable. If a load of university students keep sharing a private sexual image without the consent of the person depicted, each one could be individually guilty as the prime defendant.

In a civil action, the client initially funds the proceedings rather than the Crown Prosecution Service. If the people involved are associated, an application could be made for a non-molestation order. Disclosing private images may be a breach of privacy or harassing behaviour, for which damages may be awarded. It’s also potentially a breach of copyright if the victim has taken the picture themselves, as they will automatically own the copyright to that picture.

You can contact SPITE via:

- Phone: 0207 882 3931

- Email: lac@qmul.ac.uk

- Website contact form: lac.qmul.ac.uk

The Helpline Founder

The stigma and shame that often comes with being a victim of revenge porn can make it difficult to confide in friends and family. We speak to Laura Higgins, founder and manager of Revenge Porn Helpline, a free resource, offering a sympathetic ear and practical advice and assistance in getting content removed from websites

"Online safety is my specialism. When people ask what my job is, I say: “I keep people safe on the internet.”

The first thing you need to know about Revenge Porn Helpline is that we’re non-judgemental. When it comes to revenge porn, there can be so much victim blaming, but we pride ourselves on the fact that we’re very much about saying: “Hold on a minute, you’re the victim here.”

It’s often cathartic to just talk about what’s happened, and that’s why we’re here. The conversations may start in a garbled way, and then it’s about helping them unpick the whats, whens and whos. We also run a scheme with Queen Mary’s University called SPITE, where law students give clients free legal advice.

We work closely with the internet industry, so we’re very effective when it comes to getting content removed. Social media sites have tools in place to filter content, such as Facebook’s dedicated reporting flow for non-consensual images. We worked on the language of this with them to ensure it’s appropriate for victims. In theory, if they follow that process, the image should be taken down straight away. On occasion, someone may report something and the mechanism doesn’t pick it up. In those cases, we know people to contact and say: “You didn’t take action on this report. Please can you re-visit it.” We have a nearly 100% takedown rate when that happens.

The only problem is with websites that are purely there to host revenge porn. Sometimes we have to prepare clients that we may not be able to get it removed, but we always try our hardest. However, if the victim is under 18, they legally have to take it down.

From our point of view, a victim is a victim, and we will do everything we can to help

Technology is a part of all of our lives, so it makes sense that it’s a part of our relationships too. Couples who have been married for 10 or 15 years share images, and we do get a lot of clients in their 40s. It’s not just young people, and not just women. A quarter of our calls are from men. We get quite a lot of male, celebrity victims who have got into “honeytrap” situations. From our point of view, a victim is a victim, and we will do everything we can to help.

This year our call numbers have gone up by 50%, and the average length of calls have doubled. After the recent Rob Kardashian story, we had a lot of clients calling after recognising that what happened to them wasn’t OK.

We’re not defined by the legal definition of revenge pornography, so from our point of view the content doesn’t have to be explicit. Even if it’s just suggestive, if the client is unhappy about it being online, we take action. People’s first priority is just to make it go away, and that’s where we’re very effective. We hate the idea that once something’s online, it’s there forever. Because it’s not, and we do a really good job of making sure it’s not.

The Professor

Clare McGlynn

Clare McGlynn is a Professor of Law at Durham University, specialising in the legal regulation of pornography and image-based sexual abuse. Clare discusses the term ‘revenge porn’, and what more governing bodies can do to support victims

"The term “revenge porn” fails to cover all the different ways in which intimate photos and videos are created and shared without the consent of the people in them. Images might be shared to make money, for notoriety, for a “laugh”, not just revenge. And perpetrators are not just ex-boyfriends, but hackers, opportunists, neighbours, and former friends. Victims describe their experiences as forms of sexual assault or abuse: the images are sexual, the abuse is sexualised, and it is about non-consent.

“Image-based sexual abuse” includes “revenge porn”, but also other forms of abuse like sexualised photoshopping, upskirting, voyeurism and sexual extortion. By seeing these harms as part of a pattern, we can better understand and appreciate the depth and extent of it happening. It also means that education and campaigns can be better targeted.

The language and terms we use shape our understanding, and influences public and political debates. In terms of changing the law, the term “porn” often distracts politicians, and they think only if images are “pornography” are they harmful.

It’s hard to believe, but it’s only in the last five years or so that smartphones have become so common. This has meant it’s easier than ever to take images. Consequently, it’s easier to share a photo – and easier to take one without someone noticing.

Celebrity cases, such as Blac Chyna’s, help to raise awareness, and highlight how victim-blaming our culture is. But, we must remember that these abuses happen to all women (and it is mainly women who are victims). And most don’t have the financial resources to take legal action against perpetrators. This is why we need criminal laws to challenge these actions, as well as properly-funded support services.

We can reform the law to ensure it covers all forms of image- based sexual abuse. However, these laws will only be effective if the police and prosecutors take action. Ultimately, however, what we need is cultural change such that people all agree that it’s wrong to take or share images without consent. This means effective campaigns and education. Support for survivors is vital, which is why sustainable government funding is required for services such as the Revenge Porn Helpline."

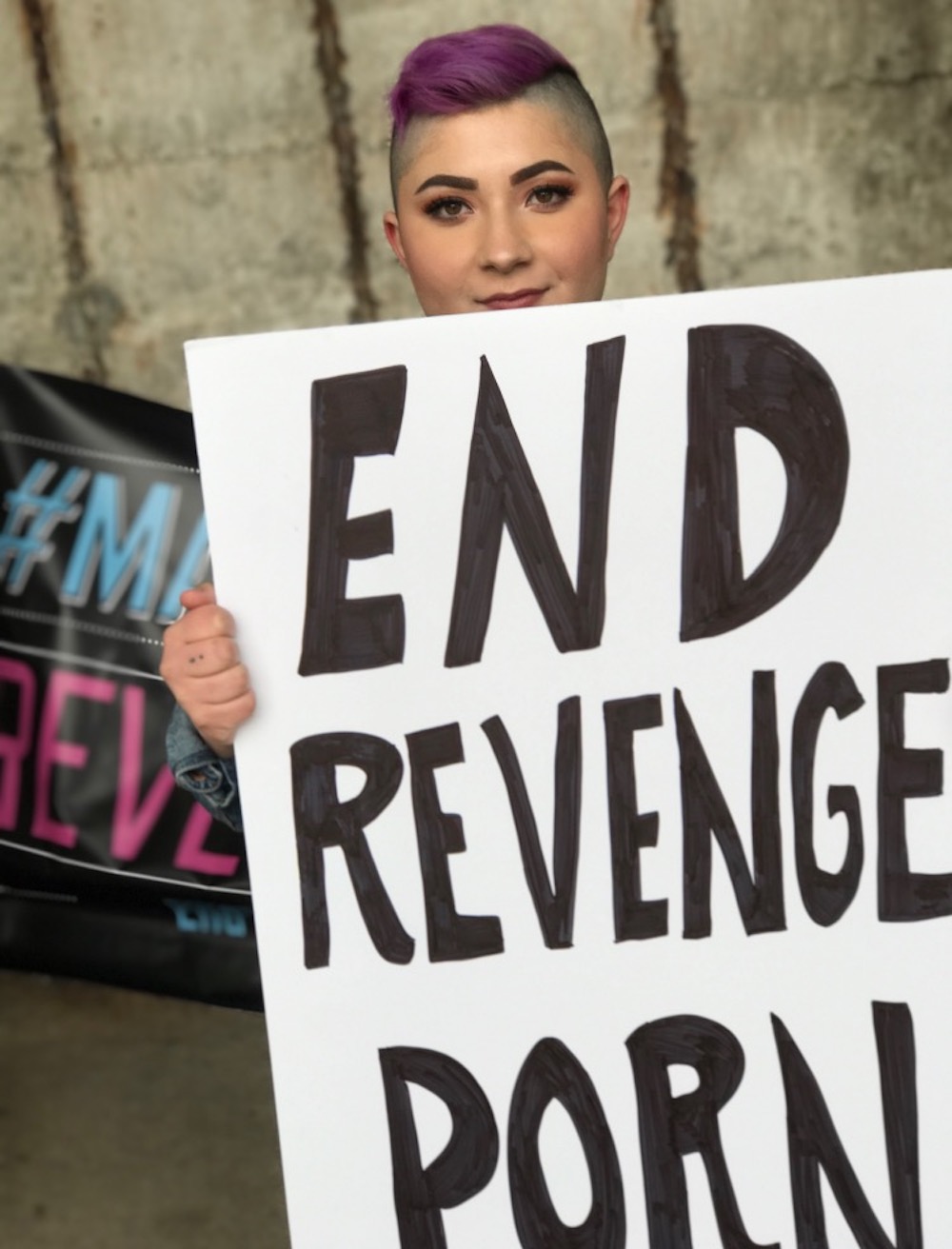

Leah Juliett

The Activist

When it comes to activism, Leah Juliett is a force to be reckoned with. They became a victim of revenge porn at 15, before founding the ‘March Against Revenge Porn’

"As a young activist during a tense era of civil rights in America, I know that having a strong voice is my most powerful tool to combat injustice. The ability to be outspoken is a privilege, and yet finding your voice after a trauma is incredibly hard.

My initial foray into activism was as a young gay person in a conservative public high school. I began volunteering for regional pride organisations and was inspired by the courage of the LGBTQ+ community in fostering areas of visibility in traditionally discriminatory locations. I was always confident in my queerness and had no problem amplifying my voice to represent others impacted by homophobia and transphobia.

But when I needed to be my own activist during my darkest time, I could not find my voice.

In 2012, at age 15, nude photos of me were posted online to humiliate me and punish me for being gay. At the time, there was no name for what was happening to me, which increased my feelings of isolation and shame. Today, the words “revenge porn” and “nonconsensual image sharing”’ are used to describe how I was exploited and exposed like a sexual trading card. I sunk into a silent depression of suicidal ideation and deep despair. I continued to advocate for the LGBTQ+ community while staying silent about my own personal trauma.

Sometimes it’s easier to advocate on behalf of others than to speak out for yourself. Five years later, I found my voice in the mugshot of the man who’d exploited me. As his picture stared into my soul, I was angered into action.

Leah Juliett

I founded the March Against Revenge Porn, a cyber civil rights organisation dedicated to helping victims of revenge porn by fostering communities of victims and allies, advocating for federal legislation, changing the narrative around cyber sexual assault, and building a base of resources. The movement began with a march across the Brooklyn Bridge. I began travelling to universities to tell my story and educate students about the impact of revenge porn. I’ve learned that revenge porn victimisation largely targets people of minority gender identities and sexual orientations, and creates a greater risk for human sex trafficking.

After holding the first march, I was noticed by national and international media organisations, and have been given opportunities to speak on CNN, BBC, MTV, Sky News, The Daily Mail, and Snapchat.

Being an activist has been both therapeutic and daunting. Despite the attention I’ve garnered, revenge porn still remains a highly underserved social issue. Nevertheless, there is hope.

At age 15, I thought I wouldn’t live to turn 20. Today, I’m almost 21 years old. I am openly nonbinary and queer. I have interned for a US Congresswoman, a prestigious domestic violence coalition, and an international human rights organisation. I currently serve as a Gay & Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation (GLAAD) Campus Ambassador, and have spoken at the Human Rights Campaign national conference.

In order to get therapeutic value from my activism, I had to face the trauma that haunted my soul and silenced my voice. My experience devastated me, but I built a movement from the devastation on which I stand to tell my story."

The Call to Action

While social media companies are beginning to take note of the urgency of this crime, the numbers reveal that this is a problem on a terrifying scale.

What’s clear is that the government, with support from initiatives like Revenge Porn Helpline and SPITE, must continue to preserve the rights of victims. With the new law criminalising this action, the seriousness of this life-destroying crime is starting to be realised.

No matter the circumstance, age, or gender; once we recognise revenge porn as the abuse it is, we can take the steps to hold perpetrators responsible, and to prevent it completely. If you’ve been affected by the issues in this article, please contact Revenge Porn Helpline, SPITE, or the police.

Comments