From life’s most challenging experiences, the actor shares the lessons she’s learning as she navigates the ongoing journey of grief

There are few experiences as universal as grief. It’s something that each of us will go through at some point in our lives. But for Jill Halfpenny, that moment happened early on in life, after her dad, Colin Halfpenny, died very suddenly at the age of 33. Jill was just four years old, but the impact of the grief remained close by. Then, in 2017, tragedy returned when Jill’s partner, Matt Janes, also suddenly passed away. He was only 43.

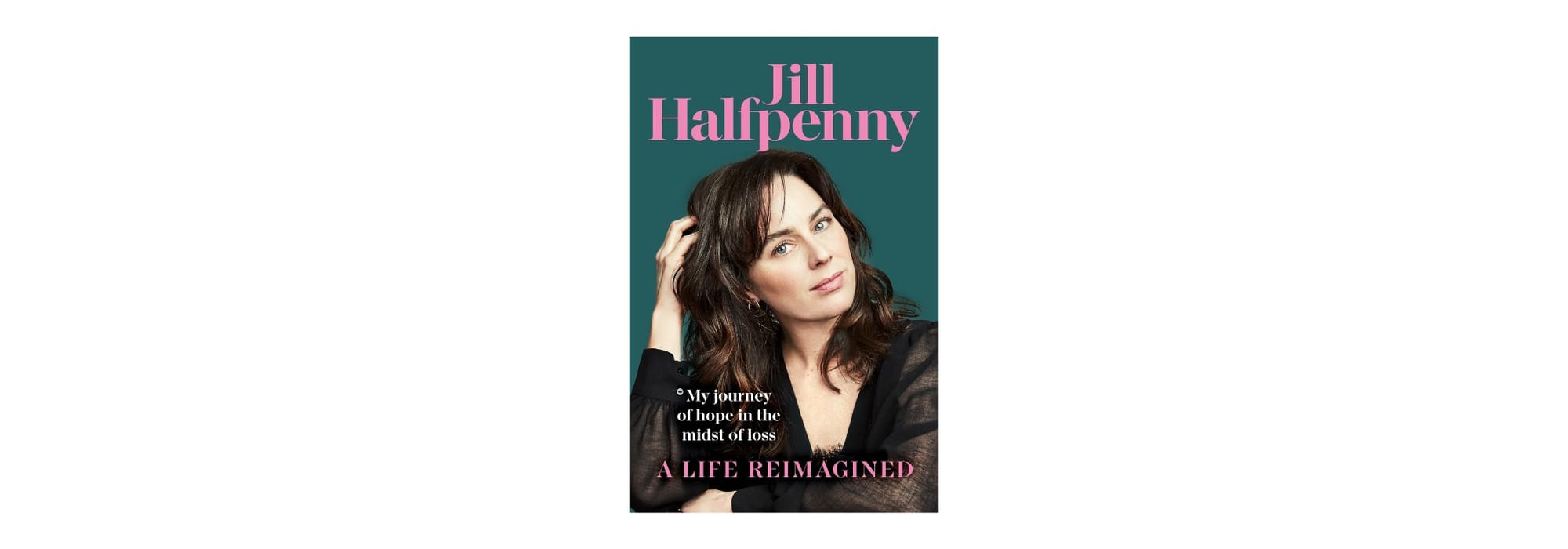

Jill has been profoundly changed by the things she has been through, something which she lays bare in her book, A Life Reimagined: My Journey of Hope in the Midst of Loss. It’s a searingly honest and vulnerable project, where Jill does not hold back from sharing the stark reality of her loss. But it’s also a celebration of the ways she has found support and shelter throughout her life – from people who just get it (and those who don’t) to wellbeing tools that have been transformative. So, what was reliving that journey like?

“I knew it would be quite cathartic, and I knew that it would take me to places that I hadn’t been for a while,” Jill reflects. “We think because we’ve thought things, we’ve processed them. But sometimes ‘process’ can take so many different forms – like saying it to another person, saying it to a group of people, saying it out loud, saying it to yourself. I got to the point where I felt like I’d learned quite a lot through my experience, and I was so hungry for connection with other people.”

This wasn’t the first time Jill has turned to the catharsis of words. Throughout the book, she shares diary entries from significant moments in her life and points to morning pages – writing three pages of stream-of-consciousness first thing in the morning, as created by Julia Cameron in her book The Artist’s Way. Meditation and exercise are other pillars of her wellbeing, as is yoga.

But while such tools have been transformative for Jill, there is sometimes a risk of viewing them as pathways to a neat destination, rather than tools to ease an ongoing journey. Society’s response to working through grief is similar – there’s an expectation to resolve it and come out the other side. In both cases, the reality is far from this, something that deeply resonates with Jill.

“Five years after Matt died, I remember speaking to a friend and she said: ‘How are you today?’ I thought, I’ll be honest, and I said: ‘I’m actually really sad.’ And I was sad, because I felt deep in grief. They said: ‘What have you got to be sad about?’ I remember thinking, so many people must really think it comes to an end. Which is strange because everybody has grief in some way or other, and everyone knows that they don’t always feel great. But I think our tolerance for people’s development, and how fast they get over something, can be difficult to deal with.

“I think that some people, whether they know it or not, are avoiders. They avoid a lot of their own pain. So if someone is an avoider, my God, they don’t want to sit with someone else’s pain. Whereas for the friends that I have that are in touch with not only their emotions, but their own vulnerabilities, and they’ve done some work on them, they can sit with you with yours and not feel like it’s a reflection of themselves. What I found was that the people who still had a lot of unprocessed grief incidents in their life were the ones that were the most difficult to spend any time with.”

Determined to do something about her own grief, following Matt’s death, Jill signed up for a five-day grief retreat with other people going through a similar thing. A mix of group therapy, exercises, and self-work – it may sound like an unusual, confrontational event, but for Jill it was pivotal.

“It was astonishing because what you were asked to do was literally to go back to the beginning of your life and map out your losses. And once you mapped them out, then the work began,” she recalls. “You ask questions like, what is it about that loss that you haven’t processed? Or what resentments are you still holding towards that person? What did that loss then do to you to make you make the choices you did? It was fascinating to go, OK, so if I lost my dad when I was four, from four onwards, I was living with this belief that people that I loved would leave me. Because of that, it also gave me the drive to make myself lovable by being successful. This is deeply unconscious though, I wasn’t actively thinking these thoughts. But I could look back and think, was that why I did the things I did? Who would I be now if my dad hadn’t died, would I even be an actress?

“The rest of the week was spent exploring how these feelings of grief and loss, no matter what the circumstances, live inside of us. You can’t think yourself out of those feelings because they’re primal. So what we had to do was choose exercises that would connect us with those feelings. There was a dance exercise where we danced for hours and hours. We kept going, to the point where you were just releasing. There was an exercise where we wrote letters to the people that we’d lost as our younger selves, that’s about bearing witness to a part of ourselves that we don’t usually listen to.

“I think people can be frightened of being in grief. They think, why would I want to go on a grief retreat? Why would I want to spend five days thinking about how sad I am? And my response to that would be, because if you give those feelings attention, you’ll be amazed at how much lighter you feel when you leave. Because now there’ll be room for other things.”

While a lot of Jill’s book explores the difficult experiences she went through and the deep and nuanced feelings and reactions she had around them, she also explores the moments of hope that she has found, naming them ‘grief gifts’.

“I think grief has made me a nicer person, and a better person,” she reflects. “It’s given me a huge amount of compassion. So when I find myself getting irritated or getting annoyed with someone, it’s like I can tap into something now where, instead of getting annoyed, I think, they’re in pain.”

It’s evident that Jill’s dedication to reflection has led her to a deep sense of self-awareness. Being able to articulate the often inexplicable feelings of grief takes time and work to come to, and yet no doubt will sound familiar to many who have been there themselves. So, after almost a lifetime of living alongside grief, and following reliving it for this book, what final lesson would Jill like to share?

“It really is OK to be OK. I remember a few years ago, somebody asked me, what do you really, really want in your life? I said the ultimate for me is to feel content. He laughed in my face, but I think living a life of contentment is the most ambitious thing anybody could ever wish for. I can’t imagine many people could step forward right now and say, I’m totally content. To me, that is success. To feel OK.”

‘A Life Reimagined: My Journey of Hope in the Midst of Loss’ by Jill Halfpenny is out now (£22, Macmillan).

Photography | Rachell Smith

Comments