A former foreign correspondent for The Times, Ed Gorman’s coverage of the Soviet-Afghan war left him with post-traumatic stress disorder. He finally found salvation in the written word

On a fine summer’s day in early August 1985, in the hills southeast of Kabul in Afghanistan, a lone Soviet army helicopter gunship came thumping and hammering its way into our valley.

I was crouching in an old foxhole cut out of the hillside by an Afghan guerrilla fighter – one of the so-called holy warriors or Mujahidin battling the Soviet occupation – and I had precious little protection as the gunship’s pilots scanned the ground in front of them.

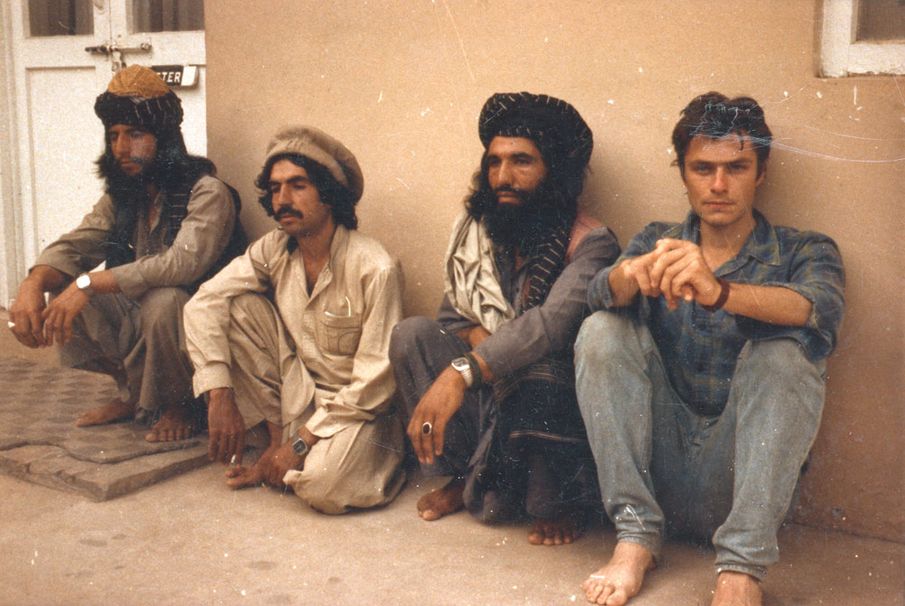

As a 24-year-old freelance journalist intent on covering my first war, this was an entirely new experience and a terrifying one at that. The gunship hovered, its front end dipping as the pilots hunted for a target.

There were several bursts from its machine gun and then the weapons system officer hit the button to release one of its rockets, which accelerated across the open air space and slammed into the hillside above me with a dull thump.

Then, as quickly as it had presented itself, the gunship turned tail and disappeared over the ridge. In its place silence returned to the hillside, then the sound of birdsong but not – I noticed – the echoing calls of the men shouting to each other to confirm that all was well.

My body would react as if I was in mortal danger – sweating, heart thumping, eyes and gums stinging. It was a waking nightmare

That episode came after several consecutive days when our camp and the surrounding hills had been bombarded by jets or by long range artillery. Even though the explosions had not caused any casualties I was feeling edgy and nervous and this time I knew immediately that something was wrong.

As the men began to gather back at the camp in a cutting in the rocks lower down from where I had been hiding, they were muttering that Abdullah-Jan, a young mullah who I relied on for translation and one of the men I had grown close to, had been killed.

He had been manning a heavy machine gun on the ridge above me and the rocket had hit him in the upper legs, causing massive injuries from which he died within a few minutes. Looking back this all sounds very frightening to witness, traumatising perhaps.

But with the advantage of hindsight and having been diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder in 1994 and successfully treated in 1995, I know that it was what happened next that formed the basis – or the core – of my traumatic symptoms.

I was stuck with men who were intent on trying to get themselves killed in battle – or martyred

Abdullah-Jan was carried down the mountain back to the camp by one of the strongest men, piggy-back style. When I first saw him it was already dusk and I was shaking with nerves after hours of shuddering explosions. There was a haunting quality to the way his head and body moved, as if life-like, as this figure made its way down the rocky path to the terrace where the men prayed.

Once there, his body was laid out and the men prepared it for burial. The commander was openly weeping as he sat alongside the bloodied corpse of his trusted lieutenant. Abdullah-Jan’s possessions were handed round as mementoes – the buttons from his tunic, his prayer beads – and I was handed his cigarettes which I immediately smoked and finished, something that would trouble me for years.

Later that evening we all walked down in silence to the burial ground below the camp where Abdullah-Jan – who was carried on a bed – was interred by moonlight alongside other men from that fighting band who had been killed in that long war.

Those images – Abdullah’s body being carried, his life-like form, the fading light, the bloodied clothing, the cigarettes – became the dominant and haunting frames in a movie that would play itself out over and over again in my fevered mind as I struggled with the incipient symptoms of PTSD for nine years before diagnosis.

I could be in a restaurant somewhere – perhaps in New York, or back in London – and suddenly a quality of the light, or a smell, or something overheard – could tip me into this other world. My mind would take me back to Logar and my body would start to react as if I was in mortal danger – sweating, heart thumping, eyes and gums stinging. It was a waking nightmare and I would feel paralysed, almost stoned, as my mind tried to cope with raw fear, years after the events that caused it. What happened to me when I was awake was mirrored by what happened when I was asleep. I would experience nightmares and terrors from which I would emerge soaked in sweat, exhausted and confused.

My case of PTSD was not caused by that episode alone. What happened to me was that, as a result of a series of rash decisions born out of inexperience and unfettered ambition, I hugely ramped up the already considerable challenge of travelling and living with the Mujahidin. In those days the only way to cover the war was to travel inside the country on foot from Pakistan and take your chances with guerrillas who were prepared to show you what they were up to in their battle against the Soviets. But they could just as easily betray you, or kill you, or hand you over in a swap for prisoners.

In my case, once inside Afghanistan, I decided to split from two fellow journalists that I entered the country with and, in doing so, lost the vital services of the man who had come in with us to act as our translator. In his place Abdullah-Jan fulfilled that role but with his death, I completely lost any control over my destiny and my ability to communicate.

From that point on I was stuck with men, many of whom were intent on trying to get themselves killed in battle – or martyred. Under fire for the first time with them, this came as an unnerving shock. I endured successive periods of bombardment by Soviet forces, then travelled secretly into Kabul and stayed in safe houses run by the resistance for 10 days and contracted dysentery. Taken together that trip “inside” lasted more than 60 days, and its cumulative impact was to leave me with permanent and slowly deteriorating trauma symptoms.

During the years that I lived undiagnosed, I continued to work as a war correspondent for The Times, completing assignments in places like Sri Lanka, Afghanistan and Bosnia and I was, for four-and-a-half years, the paper’s correspondent in Northern Ireland. Little did I know that I was doing exactly the wrong kind of work, given my condition. I assumed that the demons I was battling were normal for people in my line of work, but there were telltale signs that, in retrospect, clearly indicate something serious was wrong.

My marriage failed within months; I kept suffering strange fever-like symptoms while on assignment in places like Sarajevo or Iraq; I found I became paralysed by this fever even when simply driving to Heathrow to catch a plane to Pakistan. I was drinking heavily and relied on recreational drugs to try to numb the feelings that were still dominating my conscious and subconscious thoughts.

Luckily for me, I finally did something that dramatically converted my underlying symptoms into a full-blown crisis when, in psychiatrists’ terms, I became “non-functional”.

In early 1994 I was commissioned by The Times to return to Kabul to cover the civil war. During that trip I visited the safe houses where I had been hidden nearly 10 years earlier and was shown one of the holes under the floor of a building where I had been concealed for hours at a time when soldiers came round, hunting for guerrillas. I also discovered that two of the key people who had looked after me in 1985 had been killed, including the commander of the rebel group I had travelled with.

A key difficulty in diagnosing PTSD is that sufferers avoid talking about the core experiences that caused it

The net effect when I got back to London was that my PTSD overwhelmed me and I knew immediately that I could not work. It took a year for me to be correctly diagnosed. In those days, few doctors in London were familiar with PTSD and for many months I was misunderstood, with my doctors convinced I was presenting with a severe form of depression. One key difficulty in diagnosing PTSD is that sufferers avoid talking about the core experiences that caused it, making it harder for doctors to get to grips with what is going on.

Once correctly diagnosed, I was treated with group therapy at a two-week residential course with three other PTSD cases at a hospital in Sussex and I quickly made progress. But I was warned by the psychiatrists running the course that the scars would always remain and they were right. For years I continued to suffer flashbacks and relapses but I learnt to deal with them with my wife – I re-married not long after being treated – acting as my debriefer.

Those scars prevented me from writing about, or even talking about, what had happened to me for 28 years. Then in 2013 I finally felt able to sit down and write a full account of 1985 and my long journey to recovery that ended with the therapeutic and cathartic experience of getting it all down on the page.

I hope that my book will encourage other victims of PTSD to realise that it is possible to escape the cage in which the mind is trapped when that condition takes hold, and that a new life can be fashioned from what is left.

Ed Gorman is the author of Death of a Translator, published by Arcadia Books on 15 June.

For more information visit Arcadiabooks.co.uk

Comments