Journalist Martin Warrillow lived a fast-paced, high-pressured life in his dream job, until his mind and body reached breaking-point

The human brain can only be worked so hard. When it’s had enough, it goes haywire. A good analogy is to say it explodes. The only job I ever wanted was to be a journalist, and despite being born with spina bifida and hydrocephalus, I fulfilled that childhood wish. I spent 23 years working on local newspapers in the West Midlands, including The Tamworth Herald, The Sutton Coldfield Observer and the Birmingham Post and Mail, with most of them spent on the sports desks of major regional morning newspapers.

I loved it, but worked ridiculous hours. It was evening shifts, starting at 3pm and finishing whenever we finished, which was usually between midnight and 1am. We worked almost every Sunday and Bank Holiday because of the busy sports programme on those days. This routinely meant I didn’t get home until 1.30am, and rarely went to bed before 2am.

With my wife, Carmel, waking at 6am to get ready for her commute to work, this meant I wasn’t getting a lot of “proper” sleep. I was also eating a bad diet “on the run” – no breakfast, something quick at lunchtime, and sandwiches and crisps at work. In hindsight, it was a recipe for disaster and in 2006–7, I started to experience epileptic fits. And not just small fits, but gigantic “fall out of bed, roll around on the floor, lose control of your bodily functions” seizures.

At the age of 49, after two-and-a-half decades in the high-pressured world of journalism, my body and brain had cried, 'Enough!'

I had at least 10 of them and it took the doctors 18 months to work out what was happening. Finally, my employer paid for a private consultation with a professor of neurology. To be honest, I think they were frightened about what would happen if something really dramatic went wrong and they were shown to have not fulfilled their duty of care to an employee.

I will never forget the day I sat in the consultant’s office and he said, “You don’t know how close you’ve come to killing yourself. Your eating and sleeping patterns are wrecked. Your body clock’s shot to bits.”

Sensing disaster ahead, the company quickly put me on regular day shifts for a while and things calmed down. They also put me on a veritable feast of medication and, as I write, I haven’t had a fit since February 2010. But at the end of 2009, my department was the victim of cost-cutting in the newspaper industry as the internet took all their classified advertising, and my job was made redundant.

I lay in the road helpless, paralysed down my left side, carrying a £2,000 computer in my right hand and with a 47-seater bus headed towards me

I moved into the world of freelance journalism and quickly got a decent annual contract editing the quarterly magazine of British Naturism. Yes, British Naturism, the organisation who promote social nudity as a leisure activity. My wife and I had been naturists since stumbling on to a clothes-optional beach while on holiday in Spain in 1991, so it seemed like the perfect job.

And indeed, I enjoyed it for the first three-and-a-half years – until the 1% of the organisation’s membership who voted in leadership elections decided to change the chairman. The new incumbent hated me and office politics came to the fore. We had endless arguments over trivial issues – and naturism is supposed to be a fun leisure activity aimed at reducing stress. In the autumn of 2013, I decided not to apply for another annual contract, but before I could leave, the organisation decided not to renew my deal – and I was informed of that decision in a two-minute phone call one Sunday night, a month before Christmas.

That took away 90% of my income in one fell swoop and over the following two weeks, I’ll admit that I panicked about replacing it. I stressed too much, I worked too hard, I networked too much, doing at least five networking meetings a week, and was spending money I didn’t have. In hindsight, I took my brain and body to their limits and beyond.

Then, while I was crossing a road near my home in Tamworth, Staffordshire, on the afternoon of Monday 16 December 2013, I collapsed without warning.

I lay in the road helpless, paralysed down my left side, carrying a £2,000 computer in my right hand and with a 47-seater bus headed towards me.

I’d had a stroke. At the age of 49, after two-and-a-half decades in the high-pressured world of journalism, my body and brain had cried “Enough!”

The stroke could have killed me. The bus should have killed me. But somehow the bus miraculously missed me, and I’m still convinced to this day that the driver didn’t know I was there because I was in his blind spot. I survived the stroke.

I spent a month over Christmas and New Year in hospital, where for the first two weeks I was wholly paralysed down my left side. I was in a wheelchair for four months and I was on sticks for 18 months. It took two years for me to re-learn how to walk, which I still do with a limp, and I’ve been left with long-term and short-term memory loss and severe balance issues. But at least I’m alive.

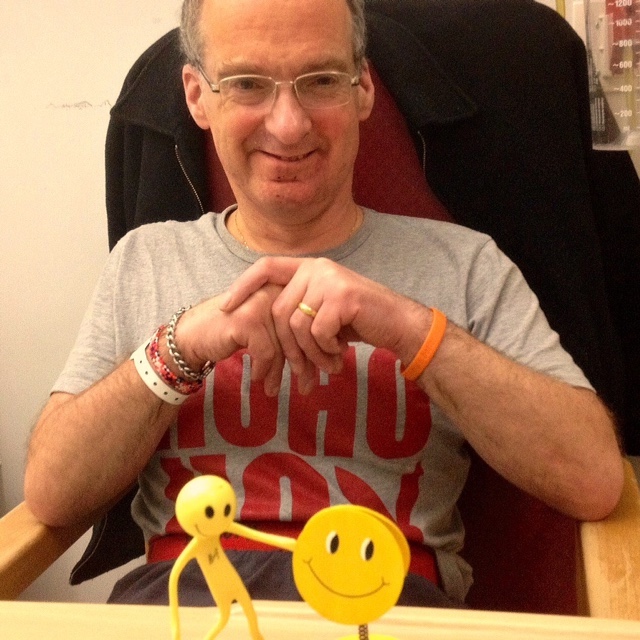

I’ve been retired from full-time work since December 2015 because of the brain damage, but use my experience on a panel for the Stroke Association to help allocate their funds for academic research. I also blog about stroke education at askthewarrior.com, and do inspirational talks about stroke education and awareness as “The Warrior”. Getting involved with support groups and just talking to other survivors online and in person can make a massive difference to your outlook in recovery. I specifically want to emphasise the need for self-employed people to take care of their brains and bodies. I point out that 20-hour days or 100-hour weeks aren’t macho – they’re stupid and dangerous – and also that people should prepare financially for the life-changing event “that will never happen to me”.

Well, I’m living, breathing proof that it can happen to you if you work your brain and body too hard. And if I can help one person avoid going through what I’ve been through over the last three-and-a-half years, and will have to go through for the rest of my life, I see that as creating a positive out of a massive negative.

Face: is their face drooping or are they unable to smile?

Arms: are they struggling to lift their arms and keep them up because of numbness or weakness on one side?

Speech: do they have slurred speech?

Time: if you notice these symptoms, it's time to dial 999.

Comments