Marissa Pendlebury overcame years of self-hatred and anorexia to discover self-love, compassion and a nourishing sense of wellbeing

I’m in my dad’s car, refusing to wear a seatbelt while he speeds down a busy starlit highway. I force my hand to grip the door handle while imagining what it would be like to open it – and jump. It was 2009, and I was 14. While everyone else thought I had the whole world ahead of me, I wished for nothing more than to shatter into a thousand pieces on the tarmac below.

Although I didn’t realise it at the time, I had been suffering with anorexia nervosa, depression and body dysmorphia for the past year. In a final attempt to get me to eat something, anything, my dad was frantically trying to drive me to a mental health hospital in the hope they would admit me and get me well. All prior attempts from my family, friends and professionals had failed, and a chance of hope seemed bleaker than bleak.

As I looked outside the car window, I believed the aftermath of jumping out would be less traumatic than being forced to eat or try and live the life I felt was ruined and not worth living for anymore.

An hour earlier, I was standing in the kitchen, in front of the fridge doors, with my parents shouting and begging me to eat. We had come to the last straw, and I knew I needed help. I wept uncontrollably because I had a deep-rooted fear of food and didn’t know how to eat without an extreme explosion of guilt, shame and anxiety. I couldn’t and wouldn’t eat, just like the many similar situations that had plagued my existence for the last several months.

Secret missions of hiding food were my main daily goals, scared of what might happen if I dared to eat something fattening or with “too many” calories. I would spend hours in a supermarket, unable to make a decision over which type of cereal to buy, meticulously calculating all the micro and macronutrients on every single packet. I would feel guilty over experiencing the simplest of pleasures. At school, getting anything but an A grade would feel catastrophic, resulting in more excruciating punishment to the body I hated.

The loved ones around me said they could no longer bear to see a lifeless shadow of myself staring back at them through hollow eyes. Yet I laughed in the face of the psychiatrist who had diagnosed me with having anorexia nervosa just a couple of weeks earlier, telling me that if I didn’t begin to eat or regain any weight, then my time left on this planet was severely limited. I didn’t realise at the time that eating disorders have the highest rate of mortality of any mental illness, but that couldn’t be me surely? To be honest, I had lost all sense of who the real me was.

I had a deep-rooted fear of food and didn't know how to eat without an extreme explosion of guilt, shame and anxiety

For myself, just like so many young vulnerable individuals in society, I remember feeling so anxious throughout my teenage years. I felt hollow, unfulfilled and never ever good enough in relation to my peers. Having legs like “tree trunks”, and curly hair like “medusa”, were regular bouts of name-calling that deeply entrenched themselves within my mind. Then we were expected to choose our GCSE options. I barely knew what cereal I wanted in the morning, never mind what type of career to pursue!

The day I returned from a teenage summer camp during 2007, I remember feeling utterly rejected. I had been isolated throughout the whole trip and left alone for the reason, I believed, of not being the pretty or popular one in my group. Then came the words, “Goodness, haven’t you put on weight,” by a close friend. That was the final straw that led me to question my existence. I began to tell myself the following:

“I am unlovable because I look ugly.”

“No one will ever like me.”

“I am worthless and unlovable.”

“I need to lose weight or else I will be destined to feel alone and unlovable forever.”

I quit running and music to focus 100% on school work and “eating healthily”. Sometimes, by the time afternoon came, I found that I hadn’t even had time to eat – a recognition that gave me a stark sense of competence, control and pleasure. Friends also positively commented on my recent dramatic weight loss – when I was only 14! For once in my life I felt like I was one step closer to being accepted by others.

Food had suddenly become everything – and nothing. A dramatic plummet in my body weight became apparent to everyone but me. Instead of seeing the gradual emaciated body and bones jutting out of my hips and spine, my eyes saw a grotesque monster staring back in the mirror.

I once thought that the choice not to eat could be easily switched off, but it soon became clear that I had no real choice. It was like an invisible force, preventing me from placing any energy into my body. Ironically, at the same time as feeling out of control, I felt in complete control. I became completely addicted to the emptiness inside my stomach that seemed to numb the anxiety and depression that plagued my every minute.

So, back to the beginning, and my dad’s car. I stared outside the window, knowing that this was it. I flung open the door, and immediately felt an excruciating pain throughout the whole upper part of my body – warm blood oozing from my shattered nose. I thought I was seconds away from death, but instead of seeing any gleam of light, I saw my dad’s arm gripped around my neck while I was half-hanging out of the car. He had swerved on the curb, puncturing a tyre, and while grabbing the cuff of my neck he inadvertently elbowed me in the face. I had been given a second chance at life, even though part of me, my eating disorder, desperately wanted me to die.

That night we did go to hospital, but A&E instead of the mental health unit. I remember my dad hugging me tightly and saying that he wouldn’t have been able to cope if I passed away. I was also fortunate enough to have many other supportive people in my life. My grandad, my ultimate best friend and life mentor, was there through everything and supported me through thick and thin. He planted those all-important seeds of love and hope in my mind.

Unfortunately, years of suffering from any eating disorder takes its toll. After five inpatient hospitalisations, being diagnosed with osteoporosis, and witnessing many traumatic events that no teenager should ever have to see, I had to grow up very quickly. On the positive side, I had been able to get significantly better, and wanted to fully recover.

In 2012, my beloved grandad passed away. On the evening of his passing, close to bonfire night, we visited a garden centre to drink tea and eat cake in his honour. I felt my grandad would have been proud of that, and it was a small comfort in what seemed like a world without any love left.

On the same night, curling up like a frightened hedgehog in bed, I heard a calm and compassionate whisper. “Marissa, you are worth loving, and have such a positive mission to accomplish. You have so much to give to others, and recovery is possible.”

I noticed that two ghostly limbs embraced my stiff body. But they weren’t that of a ghost – they were my own arms, for the first time in years, giving myself a hug. I felt safe, loved, at peace, hopeful. Even with the utter grief inside, I was overwhelmed with a sense that my eating disorder had been forcefully shown the fire exit, and that now I was free to venture upwards and onwards towards recovery. I finally felt free to find the real Marissa.

I was able to break free from my eating disorder by volunteering, pursuing new creative hobbies, and engaging in the community

I stand here now, writing this with my warm cup of tea and double chocolate digestive biscuits, knowing that the glimmer of hope on the loneliest night of my life was real.

The journey to where I am now didn’t focus on food, weight restoration or anything physical. It was about learning the vital importance of self-love and learning about the many other vital elements of wellbeing that make humans truly happy and healthy. I was able to break free from the eating disorder identity completely by volunteering, pursuing new creative hobbies and engaging in the community.

I also felt an incessant urge to start writing from my own “inner compass”. I set up a blog and wrote posts about self-love, body positivity and the many vital elements that make up health and wellness. I termed the word “compassioneer” to describe individuals who are on a journey to trust their own “inner compass” and love themselves from the inside out. I strongly believe that all of us were born to be a compassioneer.

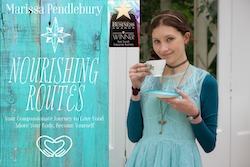

I coined the name “Nourishing Routes” to symbolise the importance of being able to go on your own unique journey to happiness and health, and finding a way to love yourself from the inside out.

The positive response I got from the blogs helped me develop a website, start a YouTube channel and even write a manuscript. Crazily, last year, the manuscript was accepted by a well-known publisher. My book was published in January.

If you believe in, and fulfil, your need for self-love, anything is possible. Health and happiness is so much more than appearing attractive or achieving society’s version of success. Trust your inner compass, follow your own unique path, reach your full potential, and heal any negative relationships with your food and with your body.

Marissa Pendlebury is the author of Nourishing Routes: Love food, adore your body, become your authentic self, available from Amazon (price £12.99).

Comments