For nearly 40 years, Dame Esther Rantzen has been a giant of television. One of the most successful presenters in BBC history – her signature show That’s Life! reached 20m viewers – she later founded the 24-hour counselling service Childline. Today, the free service helps more than 300,000 children each year. But it needs more cash, and more people. ‘There’s an epidemic of loneliness out there,’ she tells Happiful. ‘Children are calling us because there’s no one else to talk to’

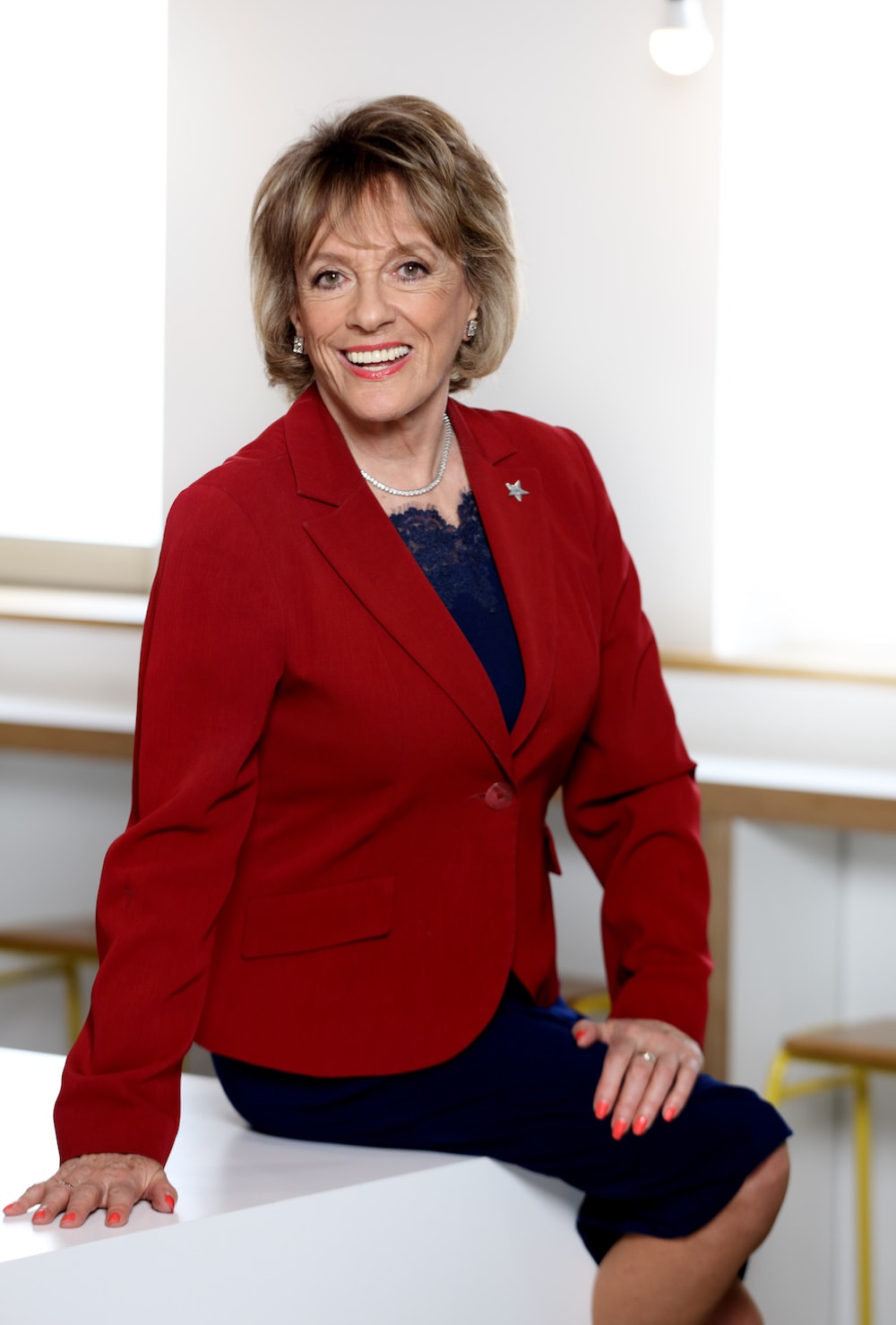

Dame Esther Rantzen

As they say, it’s multi-factorial. We need half a million pounds to answer those one in four children who can’t get through. We are also looking at our night shifts where, at about 11.30pm, there are 30 or 40 contacts from young people who are waiting in a queue for us to help them. But we don’t have enough volunteers to help. Obviously, there are money factors too. If we have more volunteers then we’ll need more staff to supervise them.

That means she’s got a high-risk caller on the line, and maybe we have to refer that child to another agency, or send an ambulance, or who knows what.

Yes, because about 73% of our contacts are now online and it takes twice as long, which means a volunteer counsellor can only help half the number of callers in their shift.

Absolutely. And we don’t know how urgent their need is, but we are desperately concerned that within that cohort of young people there are suicidal children, children with eating disorders, children who are self-harming, children being groomed. One child who was recently being groomed by someone they thought was another child (it wasn’t) into sending explicit images and videos, and now that child is being blackmailed. It can drive them to the brink of suicide.

We were able to refer the child to CEOP [The Child Exploitation and Online Protection Command] because that’s a crime.

Cash and people. That’s what we need. We’ve got 12 bases around the country, and every base needs to recruit more volunteers. Childline has around 1,500 volunteers. If you look at the Samaritans, they have about 20,000 volunteers because they’ve got literally hundreds of bases around the country. We just need to grow. We are hoping to expand and recruit more volunteers and we hope our campaign can raise more funds to pay for all for this.

[Immediately] Huge.

When we launched Childline in 1986 we were inundated with donations. Children have a much more emotional pull on the public’s compassion.

We are an extraordinary nation. A while ago people were talking about fatigue yet we raised something like £23m for Children in Need and then another £20m for one of the big disaster appeals – in a week! If you give the public good information so they trust you, then they will give – very often the poorest too.

Abusers will do anything to silence a child. They will do anything they can to prevent that child ever talking

Yes. I once got sent a gold wedding ring from a widow who said it was the only thing of value she had, and that she wanted to help children.

With children, people understand. Every time you read one of these awful stories about a child that dies, it’s a combination of huge distress and anger – “why didn’t someone save that kid?” I mean, that’s what was in my heart when we launched Childline.

Yes and yes. We did have a grant from Gordon Brown – £18m over three years to launch the online service – it was really valuable. In return they said: “You’ve got to guarantee to answer every child.” As far as I’m concerned, our principle aim is to give children what they want and need. It’s their choice, and that’s our focus.

Yes.

He was a big secret. I’m a loose cannon. The moment he died I rang up the press and said: “You need to know something about this man”.

I wanted the world to know what kind of human being George Michael was – compassionate and generous.

Now, don’t ask me questions with numbers attached because I can’t tell you, but it was a long time.

A lot. He claims he gave us all his royalties from ‘Jesus to a Child’.

I think it’s £2m, but it could be more.

BT has always helped, from the very beginning. They have always been absolutely terrific.

That’s right. Our number doesn’t show on any phone bills. We’ve got that agreement from all the providers, because they understand how crucial that agreement is. It can put children into great danger.

It’s confidential to a degree. For example, if a child calls and says she’s being abused then we do not trace that call, or ring the police, or bring in the social services. That’s because if she gets frightened by anything we do, and retracts anything she told us, then that child is in great danger. Abusers will do anything to silence a child. They will do anything they can to prevent that child ever talking about it again.

We had a child whose leg was broken by a paedophile ring. Some people had intervened, and the child was frightened, and the adults denied it, and then they broke the child’s leg and said if he ever spoke about it again to anyone they would kill him.

You must not put the child in greater danger. You must make sure children trust you and talk to you.

It’s very good.

Then we do it. One volunteer counsellor had a long conversation with a child about nothing, but clearly the child kept going, and after about 45 minutes she revealed she had taken an overdose, and told our counsellor what she had taken. At this moment, mum came home and the counsellor said: “I need to talk to your mum because you need to go to hospital.” So when a child is in immediate, life-threatening danger, then we intervene.

But 90% of the time we don’t intervene because our job is to make that child [feel] safe, and the best way is to move at the child’s pace, to move the conversation gently forward, until the child is confident and has got someone they can trust, where they can eventually ask us to refer them. Most of our referrals are with the child’s consent.

Unsurprising.

Because we knew it was much more common than anyone knew about, and that a lot of the time it was [taking place] in the family. Children were unable to talk about it because they thought nobody would believe them, or felt they were to blame for it themselves. It was the great taboo area – the unspoken crime.

[Thoughtful] Well now, was I? My sister, who is a trained social worker, was surprised. She said she’d never heard children describing [the abuse] in such a liberated way, because given anonymity on the phone, children will talk to you.

Absolutely! It’s a huge step. The first thing our counsellors do is to tell them how brave they are.

It’s a question of what children are telling us. You can say, numerically, it was sexual abuse and then it was bullying, and now it’s family relationships and mental health. But that is a sort of rough guide, because within that you can look at other trends. Abuse by adult women, for instance. That isn’t talked about at all.

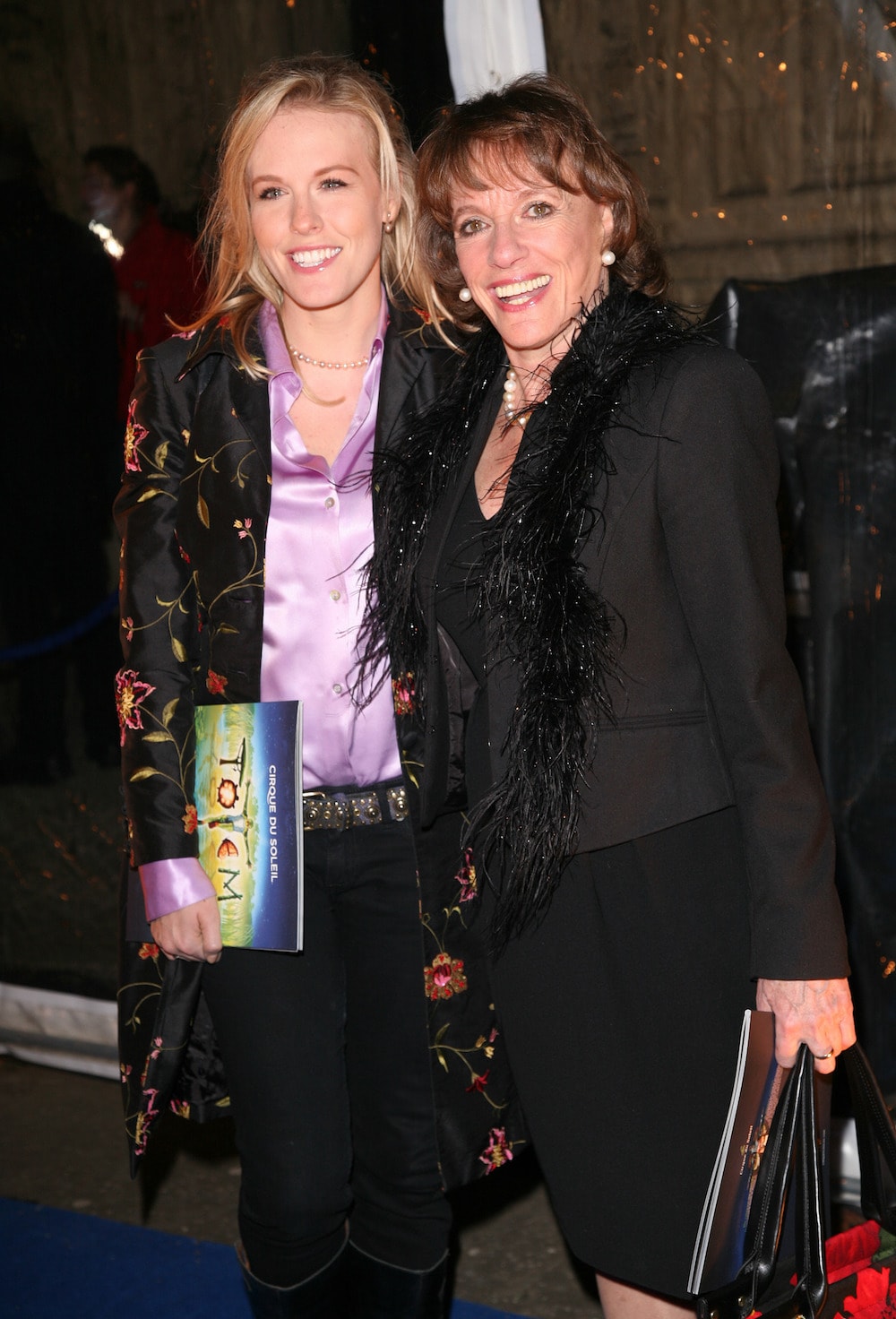

Esther and her daughter Rebecca

With adults, I can’t bear it. It happens in organisations and I can’t bear it. With children and young people, it can lead to suicide. It needs to be taken very seriously and it requires adult intervention to stop it. If you ignore it, it won’t go away. So many adults want to ignore it, hoping, that it will go away because you don’t want to make it worse. And if you do intervene then sometimes it can lead to retribution. But what we’ve got now is cyber bullying, thanks to the internet, which means children can’t escape it.

Well, what hasn’t been talked about – even by us yet – is the number of children who hear voices. So we are talking about serious mental health issues. And children talk to us because they don’t feel they can talk to anybody else about it. They think they would be written off as mad. This is an area of stigma.

Yes, in every shift. This was more or less unknown in 1986.

What the counsellors are telling us is social media – the illusion that it makes everyone feel a failure because they’re not attractive enough, they’re not beautiful enough, they haven’t got as many likes as their friends, or whether they are talking online about self-harming in a way that it provides a relief from pain. I don’t know. I find it incomprehensible myself, because I never came across it as a child. I don’t understand it.

Self-esteem is involved when a child is being bullied, or even if the bullying is just – I say just – emotional or mental. It’s an attack on their self-worth. They are attacking the child’s confidence. With that abuse, the child thinks they are to blame for it. We tell them first of all it’s not their fault. But again, some of it is social media.

We have to make time. Ad we have to pay attention. Thats what the children are telling us. They are calling Childine because there's no one else to talk to

We as a species, as human beings, didn’t evolve with mirrors and cameras. If we were to destroy every camera and mirror in the world, I think we would be happier people.

If you were to ask me what one big change has created what I describe as an epidemic of loneliness, then I think it’s about the loss of the extended family, and the loss of community. My daughter, who is a full-time mum, took her toddlers to the playground the other day and there was no one to talk to! Times gone by, sisters or friends would have gone with her.

More marriages are breaking down and more people are on their own and more people have to be much more mobile. The time of living and dying in the same community is long gone.

Of course! That’s what we are!

[Laughing] I have, but I thought I was being quite bland.

Yes, so it seems. Let’s be frank with each other.

She bloody was! I think they are absolutely right, but I have never said “do as I do”. I’ve never said that, and I also don’t think I’m a role model.

Everybody struggles with this, and it’s got worse, not better. Working hours have got longer. Shops are open over the weekend now. There’s no day of rest anymore. One Childline counsellor asked a child caller to speak to her mother and the answer was: “I can’t talk to her; she’s always working and always tired.” Both parents are expected to be wage earners just to put food on the table. Now, I understand there is a lot of poverty. I really do understand that. All I am saying is: “Think about the kids.” Do you know what I really hate?

I hate it when [BBC Radio 4’s] Woman’s Hour, a programme I love and respect, brings on a group of women and starts a hate-fest about children. The other day the creators of that new TV series Motherland were merrily laughing about what a pain it is to have children. What? This is not the way we should be discussing our own children. As women we shouldn’t, and as people we shouldn’t.

Well, where’s my bleeding trail leading to, I ask! I am just drawing attention to the most important commodity we have – time.

Make time. Have that family meal where you all sit down together. You just need to be there to listen to children. We have to make time. And we have to pay attention. I say that to myself as well as saying it to everyone else, because that’s what the children are telling us.

They are calling Childline because there’s no one else to talk to. Listening to children is something we all should do.

Childline is here to help anyone under 19 in the UK with any issue they’re going through. Childline is free, confidential and available any time, day or night. You can talk to them by calling 0800 1111.

Comments