Tara J Lal found herself drowning in a sea of grief after both her mother and brother died, and her world and family fell apart. She spent years running and hiding from her pain, but through seeking help and addressing the hurt she’d buried for so long, Tara was able to find peace with her life and discovered a new sense of belonging

I sank to the ground, as I grabbed desperately at the soil, begging it for answers. I let out a blood-curdling scream that reverberated in the darkness. “Why?” The word hung in the cold dark air before disappearing into nothingness.

It was Christmas Eve, 1988. I had been at my local pub in London with some friends when I had been overcome by the need to escape the merriness that felt like it was strangling me. It was barely five weeks since my brother had died, and the world I knew had been obliterated.

I grew up in a family of five in north London, the youngest of three children, born to our English mother and Indian father. My sister Jo was the eldest, followed by my brother, Adam, and then me.

From right to left: Adam, Tara’s sister Jo, Tara’s father Shivaji, Tara’s mother Bridget, and Tara

I thought we were just a normal family. I don’t remember how old I was when I realised that my dad was ill though. As a young girl, I have vivid memories of him sitting in his chair in our living room, eyes closed as if he was trying to shut out the world, unable to offer me any love or attention. I would go to him in search of a cuddle, but it felt as if he was enclosed in a glass tomb. I couldn’t reach him, no matter how hard I tried. I scribbled in my diary: “Dad’s depressed, I hate it when Dad’s depressed. I always think it’s my fault.”

Mum was the backbone of our family. She battled to keep our family together through our father’s illness. Then, when I was eight, she found a lump in her breast.

In 1984, when I was 13 years old, she died and our family fell apart. Our father started acting strangely, gripped by a manic psychosis that both terrified and confused me. He was admitted to a psychiatric hospital where he was diagnosed with bipolar disorder.

The three of us children were alone in the house. None of us knew how to grieve. I had hoped that we would somehow unite, but we didn’t. Instead, we fragmented in our grief, isolated bubbles floating loosely around the universe, looking for somewhere solid to settle.

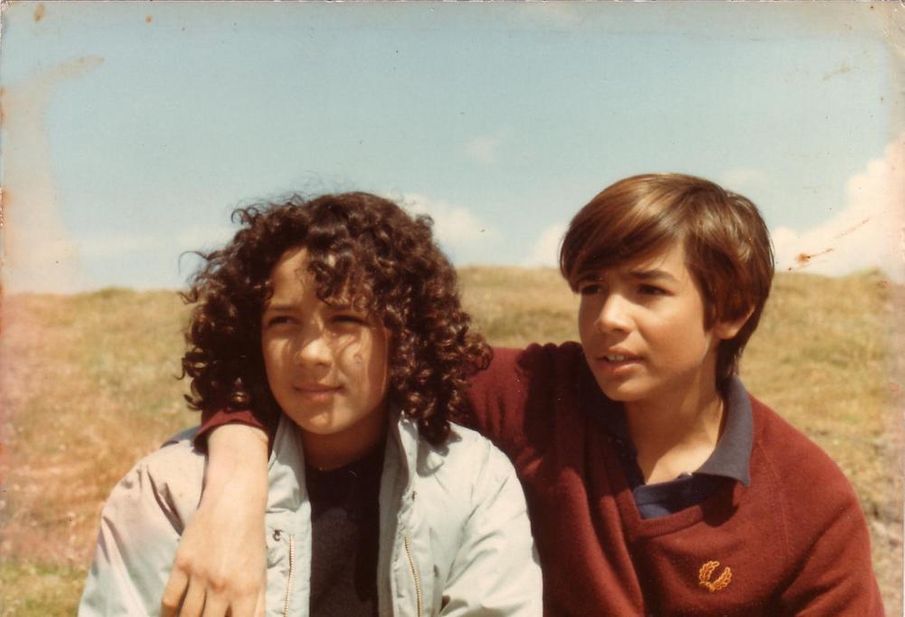

My brother became my rock. He was the person I turned to when it felt as if I were lost in a sea of grief. I admired and loved him. He was tall and handsome with beautiful Anglo-Indian skin. A straight-A student, athletic and charismatic with a quirky sense of humour, he captivated people and protected me. We had a special bond.

I don’t know when I started to notice him change. He had this terrible blank look about him. Occasionally he’d tell me he wasn’t happy, that he was worried about letting everyone down. But still, he could put on a smiling face and tell me everything would be alright. I had a feeling of foreboding; I wanted desperately to help my beautiful brother, and to drag him out of whatever terrible place he was in.

Shortly after he turned 20, four years after our mother’s death, Adam took his own life during his first term at Oxford University. It felt as if a bomb had exploded in our family home. Everything I knew and loved in the world had been taken from me.

I couldn’t breathe, I couldn’t eat, I couldn’t swallow. It felt as if I was drowning in a tsunami that never abated.

That’s how I came to be on Hampstead Heath that Christmas Eve in 1988. I wrote to a friend: “I don’t want to die, but I don’t know how to live…”

I was 17, and in my final year of school. I started getting panic attacks; it felt as if a vice was clamping around my chest, strangling my breath. The only way I knew how to cope was to keep busy, keep moving, keep travelling. I never wanted to stop. I just kept running, through my 20s, through two university degrees, all over the world. I fell in love and moved to Australia when I was 24 and became a physiotherapist.

Tara

Eventually though, I couldn’t outrun the grief, or the pain.

I was in my early 30s when I became a firefighter, with a string of broken relationships behind me. One day, we attended an incident where a young man had taken his own life. I tried to suppress an uncontrollable urge to vomit. Soon after that, a colleague attempted suicide and I had a similar physical reaction.

Things seemed to change for me when I met a man who I could see a future with. But he left me and my feelings of loss and sadness were so overwhelming and confusing that I couldn’t differentiate the past from the present. It felt like the universe was going to keep hitting me until I stopped.

Eventually, I sought the help of a psychotherapist. She guided me gently over my past, peeling back the layers I had created to keep myself safe. She helped me unlock the steel box of guilt I held in my chest. I hadn’t been able to save my brother, or my mother. In my eyes, Adam’s death was the ultimate rejection of my love; it wasn’t enough to keep him alive. I started turning towards all my fears – of aloneness, of loss, of rejection. The list felt endless, but in doing so I felt my strength emerge. At first just a flickering light, that in time became a burning flame.

I began writing my story, and saw my life unfold before me as if I were completing a jigsaw puzzle. Suddenly my life made sense. I found compassion for myself. The combination of writing and therapy was transformative for me.

I didn’t have a major epiphany, although I always wished I would. I just kept working at it. I ate well, I exercised and I kept a little book by my bed where I wrote down three things to be grateful for every night. I devoted time and energy to my friendships, which helped me feel connected. I built my own wonderfully haphazard and atypical family in Australia. I found my passion again, in nature and in sport, that enabled me to feel a sense of joy that I couldn’t remember as a child. I found a sense of belonging in Australia, through being a volunteer surf-lifesaver, through community work, and through being a firefighter.

I often think that the depth and extent of my struggle was directly proportionate to the growth and transformation that I now feel. I hope, if you are out there now, struggling, you can remember that. Never give up. Never stop searching for the answers. They often appear in the most unexpected of places.

‘Standing on My Brother’s Shoulders’ (Watkins Publishing)

I’m 47 now, and this year I represented Australia in my sport of surf boat rowing in the open women division. For me, my Australian test cap is the symbol of my struggle through adversity to become the best that I can be.

My book was published in 2015, and I now speak publicly about my experiences.

I’m still a firefighter and I volunteer my time to support those impacted by trauma. I teach mental health first aid courses and I am studying for a PhD looking at the impact of suicide on firefighters. More than anything, I see how my experiences have given me meaning and purpose in life, and I’m so grateful for that. I see how the wounds that I carry are a part of me. I no longer want to rid myself of them. They guide me. They make the tapestry of my life richer. I no longer see what life took from me, I see what it gave me.

Tara J Lal is a firefighter, mental health first aid trainer, international speaker on mental health and suicide post-vention and prevention, and the author of ‘Standing on My Brother’s Shoulders’ (Watkins Publishing). Visit tarajlal.com for more.

Two important deaths cause Tara’s world to come crashing down, and without emotional support, her family suffers and disintegrates. Tara tries to cope by running away from her grief, but it catches up with her in unexpected ways. Through the support of a therapist, she’s able to work through her feelings. Her story reminds us of the importance of taking time to process grief, to help us understand it through acceptance and compassion.

Comments