Kitty Waters buried her emotions in drink and drugs, but when her mum’s depression became too much, she transformed her life. Now she helps others from hitting rock bottom

I grew up in a household where I never really saw emotion being expressed, and it took me a long time to realise I didn’t have an outlet for my emotions. Crying, for me, was viewed as weak.

In my 20s, I got into a very high performing environment. The recruitment business was male dominated with a big drinking culture, and being a competitive person, I became one of the boys. It was the sales culture of “work hard, play hard”.

When I got upset, I didn’t know how to deal with it so I went into this destructive pattern of drinking to feel better. When I didn’t deal with those repressed emotions, I spiralled downwards and became more and more unhappy. At 22, I hit rock bottom and had an emotional breakdown.

I completely lost it. I didn’t like the way I was behaving, and I didn’t like myself. I had to take time off work, and became really detached. I’d be in a conversation but feel like I was drifting around at the top of the room. But I didn’t learn my lesson. I carried on the drinking culture, and started taking cocaine as well.

It was classic binge drinking. I wasn’t able to have one or two drinks. In my workplace, there was always somebody in the pub, so I was there every day too. I had done what a lot of addicts do, and surrounded myself with people who do the same thing because it normalises your behaviour.

We'd learnt not to deal with our emotions, and the more we internalised, the more damaging it became

There was a huge cocaine culture in London at the time, and it started off being something I did every now and again, but as you can imagine, cocaine is very addictive. I developed an association between alcohol and cocaine, so every time I drank, I craved cocaine. It was ingrained in my routine. It got so strong that I’d literally have a sip of wine and want to do a line of coke.

When I was 28, my mother became very ill with depression. She was hitting the menopause, and, like me, she’d bottled up a lot of stuff and not dealt with it. The hormonal change affected her strongly and she went into a very deep, dark depression. The female side of our family suffered with this pattern. We’d learnt not to deal with our emotions, and the more we internalised, the more damaging it became. My mum became a shell of herself.

She was a very able woman who became frail and weak. It got to the point where a highly functioning woman couldn’t boil an egg. She said: “I’m useless. I can’t even make dinner. Why do you put up with me?” All of this self-hatred culminated with me getting a phone call at work from my dad saying that my mum had gone to visit a friend, but she’d never arrived. What he didn’t tell me then, was that she’d left a suicide note.

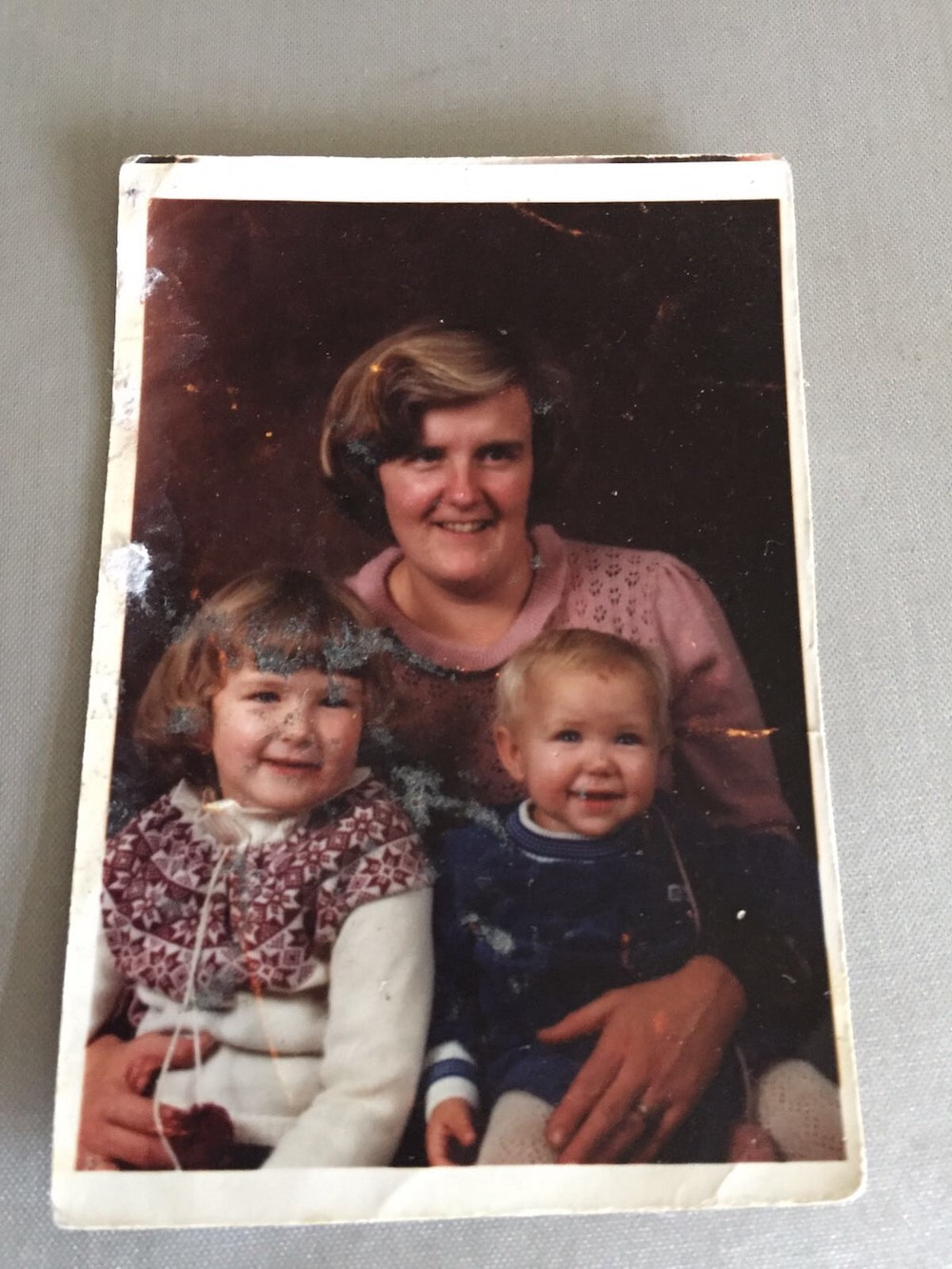

My sister, my boyfriend at the time, Dan, and I left immediately and when we arrived at my parents’ house, there was a policeman in our living room. He asked, “Has your mum ever done anything like this before?” The first shock was seeing him holding her note. My dad replied, “Yes.” I had no idea. It took until I was 28 to find out that my mum had had very bad postnatal depression. From when I was born until I was eight years old, she was in and out of hospital. She was so bad that she even tried to kill herself back then. I suddenly couldn’t even recognise my own life.

Every time I drank, I craved cocaine. It got so strong that I'd literally have a sip of wine and want to do a line of coke

We went to look for mum. There was an expanse of woods at the back of their house and to go to my mum’s friend’s house, she would have gone straight through. Since she didn’t get there, we had a feeling she was in the woods somewhere. A voice in my head said: “Turn right.” I knew with everything in my being that we had to turn right, and we were guided to where she was.

Mum had overdosed by a river. She’d taken pills and alcohol and was slumped over on her side, but luckily she hadn’t fallen in the water because she would have died. My boyfriend Dan was a paramedic, and thankfully he was there and knew what to do. I really believe he was in our lives for that reason.

Dan started doing a sternum rub while we called an ambulance. We didn’t really know where we were, so my job was to get the ambulance. I was overweight, unfit, smoked and drank, so running was hard. I remember talking to whoever was up there saying: “Please god, let her be OK, and I promise I’ll not live like this.”

Mum survived, but I didn’t cry about the situation for three weeks. I was in shock, and being the oldest in the family, I was trying to make sure everyone else was OK. A few weeks later, I got counselling through work. The counsellor was really great because she talked it all through with me, and pointed me in the direction of things I could do to process what happened. That lead me to a real journey of personal development. I realised I wanted to change and I had to dig myself out of the toxic environment I’d created around me.

Over the next few years, I changed my work environment, my friendship group, and I stopped drinking for six months. When I gave up alcohol, I didn’t need to do the cocaine. The six months I gave it up for was enough to get me out of the environment and break that association between the two.

I joined the YES Group in London for entrepreneurs and people who are into personal development. I started to socialise without alcohol for the first time. When you start to shift out of a self-serving life, you start to realise we’re here for a bigger purpose. Having gone through an experience like I’ve gone through, I didn’t want others to fall into the same trap. I didn’t want other people to hit rock bottom.

Mum had overdosed by a river; she'd taken pills and alcohol and was slumped over on her side

When the YES Group announced that they were going to climb Mount Kilimanjaro, I thought what better thing can I do to get me out of my environment?

The man who took us up the mountain was a member of the Transformational Leadership Council started by Jack Canfield – author of Chicken Soup for the Soul – and every night he’d tell us stories about the organisation and the inspirational authors and speakers who are a part of it. I was inspired to set up an organisation for people having a positive impact on the planet myself. Five years ago, I started the “The Network”.

From interacting with all these amazing people, I set up my podcast, Kitty Talks. After five years developing an amazing network of people, I’m now interviewing them to inspire others. These people are doing what they can’t stop thinking about, and it’s very much out of their heads and in their hearts.

We believe that if you listen to enough of these stories, you’ll get the courage to say this is doable. People will step into their greatness. Never give up hope. It’s really important to look at your environment, and whether it’s serving you, because that’s monumental. With Kitty Talks we create a community of people who want to make a difference. A community of like-minded people. They’re my positive tribe.

Kitty’s story reminds us that wherever we are in life’s journey, it is never too late to turn things around. Seeing the effect burying emotions had on her mum’s life gave Kitty a wake up call. Professional support enabled her to view things more clearly. Not only did she find the strength to transform her own life, she now inspires others to do the same.

Comments