Following the deaths of both his parents, Jason felt immense pressure to be ‘the man of the house’, and to bottle up his emotions. But, with time, he discovered the healing power of vulnerability

What is your most vivid childhood memory? Mine is from 15 May 1997. It was a chilly spring day in Chicagoland. The sky was painted an abstract portrait of greys, whites, and yellows. The home, where glorious memories were once made, had now been converted into a makeshift hospice. My dad, my hero, lay in a hospital bed, drifting in and out of consciousness. He had only been sick for a few months, but the end was near. The cancer had ravaged his body, much like how this event would eat away at me for years to come.

I arrived home from school and came to his bedside. I was able to hold his hand one last time as he whispered, “I love you, Jason.” His body, yellow from jaundice, looked like a fragment of the man I once knew. This was my last memory with him. He breathed his final breath a few minutes later, and life changed forever. That is the memory that defines my childhood. It quickly trumped the joyful ones of holidays and fishing trips. My hero, my innocence, and my naivety died that day.

“You’re the man of the house now,” he said just a few weeks prior, as Mom and I left the hospital. At 11-years-old, I needed to take care of Mom, who was chronically ill herself. My childhood was over. I needed to be an adult. The top priority was making sure Mom would be OK. To do so, I put up a front. I began to mask my inner fears and feelings because I could not appear weak. I started to lose touch with who I was, but chalked it up to just growing up under special circumstances.

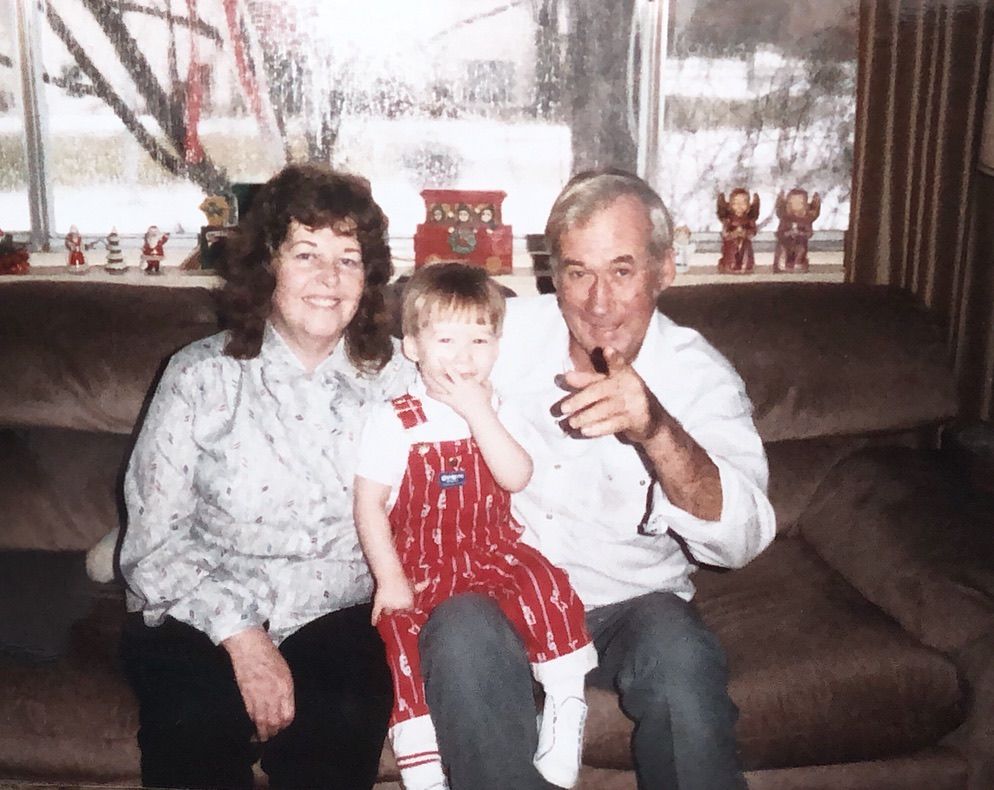

Jason with his parents as a child

Fast forward to 2005, and it felt like my life was a terrible rerun. Mom, my last pillar, slept in a hospital room full of beeping machines and rattled breathing. After two successful battles with cancer, she was about to lose this one. I was only 19 – what the hell was I supposed to do? I was not prepared to be an adult yet. The wounds from Dad’s death were still fresh.

I held her frail hand, she reminded me to let the dog out, and then she joined Dad. I was alone, really alone. My siblings had turned on me. They seemed like the enemy now. There was an age gap in our family, and I was the youngest by 15 years. They did not approve of my new party lifestyle. I didn’t approve either, but it was the only way to feel somewhat my age and escape the pain I felt.

I faced eviction, arrest, a nasty estate battle, and a few dead-end jobs in the aftermath. I felt broken, I felt useless, but above all, I hurt.

I had lost my parents. My childhood memories felt tarnished. Meanwhile, the rest of my friends were living their best lives at college while I struggled to survive.

Did I ask for help? Did I let others into my world of pain and inner turmoil? No! I needed to stay ‘the man of the house’. Act tough, put on a brave face, and impress others with my resilience. I turned to alcohol a lot. It temporarily numbed the pain. I was that obnoxious, loud friend, always up for another beer. I lied to myself that this is who I was and wanted to be.

In 2010, I met my future husband, my knight in shining armour. I could never understand why he loved me or wanted to be with me. I felt like I wasn’t worthy of him, and that he could do so much better than me. As such, I only allowed him to see the tip of the iceberg of my pain. I feared that my complete openness might chase him away. I had already lost too much to lose again.

This hurt eventually turned into anger. My perspective soured as the years went along. I was bitter at the world, at my family, at life for handing me this unfair deck of cards. My loving relationship with my husband grew tense. Bickering progressed into arguments and tears, usually as a result of my abusive relationship with alcohol. I turned to beer to escape my pain and insecurities, while still masquerading as a happy-go-lucky guy.

Jason and his husband, Matt, on their wedding day

In 2020, I bottomed out. My weight and self-respect reached an all-time low. My drinking and frustration hit an all-time high. My husband expressed his concerns, and in this moment of weakness, something awoke in me. He opened my eyes to the pain and hurt in my childhood, and the damage I was doing to myself now.

He recognised my pain and, in a move of independence, I did too. I realised I was broken. I ached. I needed help. The following Monday, I called my doctor and started my road to recovery. I began working through personal issues with my therapist, who helped me better understand my anxious and OCD thoughts, thus enabling me to address my disordered eating. We talked about how I never had a chance to eulogise my parents, my jealousy about never having a normal childhood, the pain of losing my family, and how the fallout from the estate battle left the good memories tarnished.

My therapist helped me open up and face problems I didn’t know I had. In turn, I began to embrace vulnerability; I felt empowered each time I let my guard down. I found the strength to take the upper hand with my eating disorder, to cope with the pain I buried away. I reconnected with the parts of me I always loved. I remembered who I was before life’s vicious attacks commenced.

I’ve always enjoyed writing, and found this as my outlet to speak my truths. Through writing, I learned that ‘the man of the house’ can show vulnerability. That does not equal weakness but, instead, it shows love for himself and those around him. I can be honest with myself now, with my husband and with my friends. I broke free from the chains of my eating disorder, my insecurities, and the hurtful memories.

Vulnerability is defined as the state of being exposed to the possibility of being attacked or harmed, either physically or emotionally. All along, I was the one doing the attacking and harm to myself by not allowing myself to share my struggles. I am now on a mission to help others live their best lives, just like I am finally doing after two decades of inner hell.

Rav Sekhon | BA MA MBACP (Accred) says:

Jason’s inspirational story provides insight into how difficult life events at an early age can have a damaging impacting our self-esteem. The trauma Jason experienced was evidently very challenging, and he used alcohol to cope. However, over time, with a supportive husband and access to therapy, Jason was able to work through his past and challenge the stigma of what it means be a man. Jason is living proof that men can be vulnerable, and this is a true sign of strength.

To connect with a counsellor to discuss ways to navigate grief, or ways to manage addiction, visit counselling-directory.org.uk

Comments